サイクリン依存性キナーゼ2

サイクリン依存性キナーゼ2(サイクリンいぞんせいキナーゼ2、英: cyclin-dependent kinase 2、略称: CDK2)は、サイクリン依存性キナーゼ(CDK)ファミリーに属するセリン/スレオニンキナーゼである。ヒトではCDK2遺伝子にコードされる[5][6]。CDK2は、ヒトのCDK1や、出芽酵母Saccharomyces cerevisiaeのcdc28、分裂酵母Schizosaccharomyces pombeのcdc2の遺伝子産物ときわめて類似している。CDK2はサイクリン/CDK複合体の触媒サブユニットとして機能し、その活性は細胞周期のG1/S期に限定される。この期間に細胞は有糸分裂とDNA複製に必要なタンパク質の合成を行う。CDK2はサイクリンEやサイクリンAなどの調節サブユニットと結合し、それらによる調節を受ける。サイクリンEとの結合は、G1期からS期への進行に必要とされる。一方、サイクリンAとの結合はS期を通じて細胞周期の進行に必要とされる[7]。CDK2の活性はリン酸化によっても調節される。複数のスプライスバリアントや複数の遺伝子転写開始部位が存在することも報告されている[6]。近年、CDK2を欠失した細胞でもG1期からS期への移行が起こることが報告され、この過程におけるCDK2の必要性には疑問が呈されている[8]。

正常に機能している組織における必要性

編集培養細胞に基づいた実験では、CDK2の阻害によってG1/S期の移行の時点で細胞周期が停止することが示されていた[9]。後のマウス胚線維芽細胞を用いた実験では、CDK2の欠失によってG1期が延長することが示された。しかし、この期間の後にはS期への進行が起こり、細胞周期の残りの期間を完了することも可能であった[10]。マウスでCDK2を欠失させたときには、生存は可能であるが体のサイズは小さくなる。一方、オスとメスの双方で減数分裂が阻害された。このことは、CDK2は健康な細胞の細胞周期には必須ではないものの、減数分裂や生殖には必須であることを示唆している[11]。CDK2のノックアウトマウスの細胞は分裂回数が少なく、そのため体のサイズが小さくなると考えられる。また、生殖細胞は減数分裂の前期で分裂を停止するため、不妊となる[10]。現在では、減数分裂の機能を除いた多くの面で、CDK2の欠失の影響はCDK1によって補償されていると考えられている[11]。

活性化機構

編集CDK2は2つのローブからなる構造をしている。N末端側のローブ(Nローブ)は多くのβシートを含む一方、C末端側のローブ(Cローブ)はαヘリックスに富む[7]。CDK2は多種のサイクリンと結合することができ、サイクリンA、B、E、そしておそらくサイクリンCとも結合する[11]。近年の研究では、CDK2はサイクリンA、Eに、CDK1はサイクリンA、Bに対し優先的に結合することが示唆されている[12]。

CDK2は、NローブとCローブの間に位置する活性部位にサイクリンが結合したときに活性化状態となる。この活性部位の配置のため、パートナーとなるサイクリンはCDK2の双方のローブと相互作用する。CDK2のNローブには重要なαヘリックスが存在し、CヘリックスまたはPSTAIREヘリックスと呼ばれている。Cヘリックスとサイクリンは疎水的相互作用を行う。活性化に伴ってコンフォメーションの変化が起こり、Cヘリックスは回転してNローブのコアの近くへ移動する。これによってCヘリックスのグルタミン酸残基と近接するリジン残基との間でイオン対が形成される。また、このコンフォメーション変化によって活性化ループ(Tループ)と呼ばれる領域がCローブ側へ再配置され、ATP結合部位が露出して新たな相互作用が可能な状態となる。活性化ループが触媒部位から移動すると、活性化ループのスレオニン残基のリン酸化が行われる。リン酸化されたスレオニン残基は、酵素の最終的なコンフォメーションを安定化する[13]。この活性化過程を通じて、CDK2に結合したサイクリン側にはコンフォメーション変化は起こらない[7][14]。

DNA複製における役割

編集細胞分裂過程が成功するかどうかは、細胞と組織の双方のレベルでの正確な調節に依存している。細胞内のタンパク質とDNAの複雑な相互作用によって、ゲノムDNAは娘細胞へ伝達される。そして細胞と細胞外マトリックスタンパク質との相互作用によって、新たな細胞は既存の組織中へ組み込まれる。細胞レベルでは、細胞分裂過程はCDKとサイクリンによって制御されている。DNA損傷などの欠陥が修復されるまで細胞周期の進行を遅らせる手段として、細胞はさまざまな細胞周期チェックポイントを利用する[16]。

CDK2は細胞周期のG1期とS期を通じて活性があり、G1/S期のチェックポイントの制御を行う。G1期に先立って、CDK4とCDK6のレベルがサイクリンDとともに上昇する。これによってG1期の初期にはRbタンパク質の部分的なリン酸化が行われ、転写因子のE2Fの抑制が部分的に解除される。その結果サイクリンEの合成が促進されてCDK2の活性が上昇する。G1期の終わりにはサイクリンE-CDK2複合体の活性は最大レベルに達し、S期の開始に大きな役割を果たす[17]。G1/S期の移行時にはRbタンパク質とp27タンパク質がサイクリンA/E-CDK2複合体によってリン酸化され、完全に不活性化される[18]。それに伴い、E2FによってS期への進入を促進する遺伝子の発現が行われる[18][19][20]。さらに、サイクリンE-CDK2複合体の基質であるNPATがリン酸化され、ヒストン遺伝子の転写を活性化する[21]。これによってクロマチンの主要なタンパク質構成要素であるヒストンの合成が増大し、S期に行われるDNA複製をサポートする。S期の終わりに、サイクリンEはユビキチン-プロテアソームシステムによって分解される[10]。

がん細胞の増殖

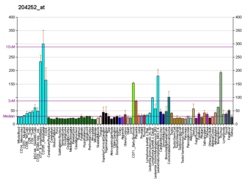

編集CDK2は正常に機能している細胞での細胞周期の進行に必要不可欠な要素ではないが、がん細胞の異常な成長過程には重要である。CCNE1遺伝子は、CDK2の主要な2つの結合パートナーのうちの1つであるサイクリンEを産生する。CCNE1の過剰発現は多くの腫瘍細胞で見られ、これらの細胞の生存はCDK2とサイクリンEに依存している[12]。サイクリンEの異常な活性は、乳がん、肺がん、大腸がん、胃がん、骨のがん、白血病やリンパ腫でも見られる[17]。同様に、サイクリンA2の異常な発現は染色体不安定性や腫瘍増殖と関係しており、その阻害によって腫瘍の成長は低下する[22]。そのため、CDK2とそのパートナーとなるサイクリンは新たながん治療法の治療標的となる可能性がある[12]。前臨床モデルでは腫瘍成長の抑制に予備的な成功がみられており、現行の化学療法薬の副作用を減少させることも観察されている[23][24][25]。

CDK2に対する選択的阻害薬の同定は、CDK2と他のCDKの活性部位の類似性、特にCDK1との極度の類似性のため困難である[12]。CDK1は細胞周期に必須な唯一のCDKであり、その阻害によって意図しない副作用が生じる可能性がある[26]。CDK2阻害薬候補の大部分はATP結合部位を標的としており、タイプIとタイプIIの2つの主要なクラスに分類される。タイプIの阻害薬は活性部位のATP結合部位に対して競合的に機能する。タイプIIの阻害薬はサイクリン非結合状態のCDK2を標的とし、ATP結合部位やキナーゼ内の疎水的ポケットのどちらかを占有する。タイプIIの阻害薬の方が選択性が高いと考えられている[24]。近年、CDKの新たな結晶構造が発表され、Cヘリックスの近傍にアロステリック結合部位が存在する可能性が示された。このアロステリック部位を標的とした阻害薬はタイプIIIに分類される[27]。他に標的として可能性があるのはCDK2のTループである。サイクリンAがCDK2に結合するとNローブが回転し、ATP結合部位は活性化され、Tループと呼ばれる活性化ループの位置が切り替えられる[28]。

阻害因子

編集既知のCDK阻害因子としては、p21Cip1(CDKN1A)やp27Kip1(CDKN1B)がある[29]。

ロスマリン酸メチル(rosmarinic acid methyl ester)は植物由来のCDK2阻害剤で、マウス再狭窄モデルにおいて血管平滑筋細胞の増殖を抑制し、内膜新生を低下させることが示されている[30]。

遺伝子調節

編集メラニン細胞では、CDK2遺伝子の発現は小眼球症関連転写因子(MITF)によって調節されている[31][32]。

相互作用

編集CDK2は次に挙げる因子と相互作用することが示されている。

出典

編集- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000123374 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000025358 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Isolation of the human cdk2 gene that encodes the cyclin A- and adenovirus E1A-associated p33 kinase”. Nature 353 (6340): 174–7. (September 1991). doi:10.1038/353174a0. PMID 1653904.

- ^ a b “Entrez Gene: CDK2 cyclin-dependent kinase 2”. 2020年1月8日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Recent developments in cyclin-dependent kinase biochemical and structural studies”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1804 (3): 511–9. (March 2010). doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.10.002. PMID 19822225.

- ^ “Cdk2 knockout mice are viable”. Current Biology 13 (20): 1775–85. (October 2003). doi:10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.024. PMID 14561402.

- ^ van den Heuvel, S.; Harlow, E. (1993-12-24). “Distinct roles for cyclin-dependent kinases in cell cycle control”. Science (New York, N.Y.) 262 (5142): 2050–2054. doi:10.1126/science.8266103. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 8266103.

- ^ a b c “Promiscuity rules? The dispensability of cyclin E and Cdk2”. Science's STKE 2004 (224): pe11. (March 2004). doi:10.1126/stke.2242004pe11. PMC 3242733. PMID 15026579.

- ^ a b c “Mammalian cell-cycle regulation: several Cdks, numerous cyclins and diverse compensatory mechanisms”. Oncogene 28 (33): 2925–39. (August 2009). doi:10.1038/onc.2009.170. PMID 19561645.

- ^ a b c d “Differences in the Conformational Energy Landscape of CDK1 and CDK2 Suggest a Mechanism for Achieving Selective CDK Inhibition”. Cell Chemical Biology 26 (1): 121–130.e5. (November 2018). doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.10.015. PMC 6344228. PMID 30472117.

- ^ a b PDB: 1FIN; “Mechanism of CDK activation revealed by the structure of a cyclinA-CDK2 complex”. Nature 376 (6538): 313–20. (July 1995). doi:10.1038/376313a0. PMID 7630397.

- ^ “Cyclin-dependent kinases”. Genome Biology 15 (6): 122. (2014-06-30). doi:10.1186/gb4184. PMC 4097832. PMID 25180339.

- ^ PDB: 1W98; “The structure of cyclin E1/CDK2: implications for CDK2 activation and CDK2-independent roles”. The EMBO Journal 24 (3): 452–63. (February 2005). doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600554. PMC 548659. PMID 15660127.

- ^ “Checking on DNA damage in S phase”. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 5 (10): 792–804. (October 2004). doi:10.1038/nrm1493. PMID 15459660.

- ^ a b “Low-Molecular-Weight Cyclin E in Human Cancer: Cellular Consequences and Opportunities for Targeted Therapies”. Cancer Research 78 (19): 5481–5491. (October 2018). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-18-1235. PMC 6168358. PMID 30194068.

- ^ a b “RB and cell cycle progression”. Oncogene 25 (38): 5220–7. (August 2006). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209615. PMID 16936740.

- ^ “Pocket proteins and cell cycle control”. Oncogene 24 (17): 2796–809. (April 2005). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208619. PMID 15838516.

- ^ The molecular basis of cancer. Mendelsohn, John, 1936-, Gray, Joe W.,, Howley, Peter M.,, Israel, Mark A.,, Thompson, Craig (Craig B.) (Fourth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. (2015). ISBN 9781455740666. OCLC 870870610

- ^ “NPAT links cyclin E-Cdk2 to the regulation of replication-dependent histone gene transcription”. Genes & Development 14 (18): 2283–97. (September 2000). doi:10.1101/gad.827700. PMC 316937. PMID 10995386.

- ^ “Loss of Cdk2 and cyclin A2 impairs cell proliferation and tumorigenesis”. Cancer Research 74 (14): 3870–9. (July 2014). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3440. PMC 4102624. PMID 24802190.

- ^ “Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiomyopathy”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 293 (51): 19672–19685. (October 2018). doi:10.1074/jbc.ra118.004673. PMC 6314117. PMID 30361442.

- ^ a b “Inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases as cancer therapeutics”. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 173: 83–105. (May 2017). doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.02.008. PMC 6141011. PMID 28174091.

- ^ “Roscovitine in cancer and other diseases”. Annals of Translational Medicine 3 (10): 135. (June 2015). doi:10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.03.61. PMC 4486920. PMID 26207228.

- ^ “CDK1 structures reveal conserved and unique features of the essential cell cycle CDK”. Nature Communications 6: 6769. (April 2015). doi:10.1038/ncomms7769. PMC 4413027. PMID 25864384.

- ^ “Structure-based discovery of the first allosteric inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase 2”. Cell Cycle 13 (14): 2296–305. (2014-06-09). doi:10.4161/cc.29295. PMC 4111683. PMID 24911186.

- ^ “Targeting Conformational Activation of CDK2 Kinase”. Biotechnology Journal 12 (8): 1600531. (August 2017). doi:10.1002/biot.201600531. PMID 28430399.

- ^ “Cleavage of p21Cip1/Waf1 and p27Kip1 mediates apoptosis in endothelial cells through activation of Cdk2: role of a caspase cascade”. Molecular Cell 1 (4): 553–63. (March 1998). doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80055-6. PMID 9660939.

- ^ “Constituents of Mediterranean Spices Counteracting Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation: Identification and Characterization of Rosmarinic Acid Methyl Ester as a Novel Inhibitor”. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 62 (7): e1700860. (April 2018). doi:10.1002/mnfr.201700860. PMID 29405576.

- ^ “Critical role of CDK2 for melanoma growth linked to its melanocyte-specific transcriptional regulation by MITF”. Cancer Cell 6 (6): 565–76. (December 2004). doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.014. PMID 15607961.

- ^ “Novel MITF targets identified using a two-step DNA microarray strategy”. Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research 21 (6): 665–76. (December 2008). doi:10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00505.x. PMID 19067971.

- ^ “BRCA1 is a 220-kDa nuclear phosphoprotein that is expressed and phosphorylated in a cell cycle-dependent manner”. Cancer Research 56 (14): 3168–72. (July 1996). PMID 8764100.

- ^ “BRCA1 is phosphorylated at serine 1497 in vivo at a cyclin-dependent kinase 2 phosphorylation site”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 19 (7): 4843–54. (July 1999). doi:10.1128/MCB.19.7.4843. PMC 84283. PMID 10373534.

- ^ “BRCA1 proteins are transported to the nucleus in the absence of serum and splice variants BRCA1a, BRCA1b are tyrosine phosphoproteins that associate with E2F, cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases”. Oncogene 15 (2): 143–57. (July 1997). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201252. PMID 9244350.

- ^ “p12(DOC-1) is a novel cyclin-dependent kinase 2-associated protein”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 20 (17): 6300–7. (September 2000). doi:10.1128/MCB.20.17.6300-6307.2000. PMC 86104. PMID 10938106.

- ^ a b “CRM1/Ran-mediated nuclear export of p27(Kip1) involves a nuclear export signal and links p27 export and proteolysis”. Molecular Biology of the Cell 14 (1): 201–13. (January 2003). doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0319. PMC 140238. PMID 12529437.

- ^ a b “Tuberin binds p27 and negatively regulates its interaction with the SCF component Skp2”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 (47): 48707–15. (November 2004). doi:10.1074/jbc.M405528200. PMID 15355997.

- ^ “Bcl-2 expression suppresses mismatch repair activity through inhibition of E2F transcriptional activity”. Nature Cell Biology 7 (2): 137–47. (February 2005). doi:10.1038/ncb1215. PMID 15619620.

- ^ “Spy1 interacts with p27Kip1 to allow G1/S progression”. Molecular Biology of the Cell 14 (9): 3664–74. (September 2003). doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0820. PMC 196558. PMID 12972555.

- ^ a b “Rapamycin potentiates transforming growth factor beta-induced growth arrest in nontransformed, oncogene-transformed, and human cancer cells”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 22 (23): 8184–98. (December 2002). doi:10.1128/mcb.22.23.8184-8198.2002. PMC 134072. PMID 12417722.

- ^ “Abolishment of the interaction between cyclin-dependent kinase 2 and Cdk-associated protein phosphatase by a truncated KAP mutant”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 305 (2): 311–4. (May 2003). doi:10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00757-5. PMID 12745075.

- ^ “KAP: a dual specificity phosphatase that interacts with cyclin-dependent kinases”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91 (5): 1731–5. (March 1994). doi:10.1073/pnas.91.5.1731. PMC 43237. PMID 8127873.

- ^ a b “The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases”. Cell 75 (4): 805–16. (November 1993). doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. PMID 8242751.

- ^ “C/EBPalpha arrests cell proliferation through direct inhibition of Cdk2 and Cdk4”. Molecular Cell 8 (4): 817–28. (October 2001). doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00366-5. PMID 11684017.

- ^ “A distinct cyclin A is expressed in germ cells in the mouse”. Development 122 (1): 53–64. (January 1996). PMID 8565853.

- ^ “Characterization of a second human cyclin A that is highly expressed in testis and in several leukemic cell lines”. Cancer Research 57 (5): 913–20. (March 1997). PMID 9041194.

- ^ “Cyclin A1 directly interacts with B-myb and cyclin A1/cdk2 phosphorylate B-myb at functionally important serine and threonine residues: tissue-specific regulation of B-myb function”. Blood 97 (7): 2091–7. (April 2001). doi:10.1182/blood.v97.7.2091. PMID 11264176.

- ^ “The structural basis for specificity of substrate and recruitment peptides for cyclin-dependent kinases”. Nature Cell Biology 1 (7): 438–43. (November 1999). doi:10.1038/15674. PMID 10559988.

- ^ a b c “Cyclin E associates with BAF155 and BRG1, components of the mammalian SWI-SNF complex, and alters the ability of BRG1 to induce growth arrest”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 19 (2): 1460–9. (February 1999). doi:10.1128/mcb.19.2.1460. PMC 116074. PMID 9891079.

- ^ a b “P21Waf1/Cip1 dysfunction in neuroblastoma: a novel mechanism of attenuating G0-G1 cell cycle arrest”. Cancer Research 63 (13): 3840–4. (July 2003). PMID 12839982.

- ^ “Formation and activation of a cyclin E-cdk2 complex during the G1 phase of the human cell cycle”. Science 257 (5077): 1689–94. (September 1992). doi:10.1126/science.1388288. PMID 1388288.

- ^ “mTOR-dependent activation of the transcription factor TIF-IA links rRNA synthesis to nutrient availability”. Genes & Development 18 (4): 423–34. (February 2004). doi:10.1101/gad.285504. PMC 359396. PMID 15004009.

- ^ “NIPP1-mediated interaction of protein phosphatase-1 with CDC5L, a regulator of pre-mRNA splicing and mitotic entry”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (33): 25411–7. (August 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.M001676200. PMID 10827081.

- ^ “Phosphorylation of human Fen1 by cyclin-dependent kinase modulates its role in replication fork regulation”. Oncogene 22 (28): 4301–13. (July 2003). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206606. PMID 12853968.

- ^ “Human origin recognition complex large subunit is degraded by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis after initiation of DNA replication”. Molecular Cell 9 (3): 481–91. (March 2002). doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00467-7. PMID 11931757.

- ^ a b “Regulation of cyclin A-Cdk2 by SCF component Skp1 and F-box protein Skp2”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 19 (1): 635–45. (January 1999). doi:10.1128/mcb.19.1.635. PMC 83921. PMID 9858587.

- ^ “TOK-1, a novel p21Cip1-binding protein that cooperatively enhances p21-dependent inhibitory activity toward CDK2 kinase”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (40): 31145–54. (October 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.M003031200. PMID 10878006.

- ^ a b “Dephosphorylation of human cyclin-dependent kinases by protein phosphatase type 2C alpha and beta 2 isoforms”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (44): 34744–9. (November 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.M006210200. PMID 10934208.

- ^ “Reversal of growth suppression by p107 via direct phosphorylation by cyclin D1/cyclin-dependent kinase 4”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 22 (7): 2242–54. (April 2002). doi:10.1128/mcb.22.7.2242-2254.2002. PMC 133692. PMID 11884610.

- ^ “Identification of a p130 domain mediating interactions with cyclin A/cdk 2 and cyclin E/cdk 2 complexes”. Oncogene 14 (20): 2395–406. (May 1997). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201085. PMID 9188854.

- ^ “Interaction between ubiquitin-protein ligase SCFSKP2 and E2F-1 underlies the regulation of E2F-1 degradation”. Nature Cell Biology 1 (1): 14–9. (May 1999). doi:10.1038/8984. PMID 10559858.

関連文献

編集- “Cell cycle sibling rivalry: Cdc2 vs. Cdk2”. Cell Cycle 4 (11): 1491–4. (November 2005). doi:10.4161/cc.4.11.2124. PMID 16258277.

- “Cyclin dependent kinase 2 and the regulation of human progesterone receptor activity”. Steroids 72 (2): 202–9. (February 2007). doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2006.11.025. PMC 1950255. PMID 17207508.