モノアミン酸化酵素B

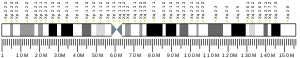

モノアミン酸化酵素B(モノアミンさんかこうそB、モノアミンオキシダーゼB、英: monoamine oxidase B、略称: MAO-B)は、ヒトではMAOB遺伝子にコードされる酵素である。

MAO-Bはフラビンモノアミンオキシダーゼファミリーに属し、ミトコンドリア外膜に位置している。生体物質や生体異物のアミンの酸化的脱アミノ化を触媒し、中枢神経系や末梢組織において神経作動性や血管作用性を有するアミンの異化に重要な役割を果たしている。このタンパク質はベンジルアミンやフェネチルアミンを選択的に分解する[5]。モノアミン酸化酵素A(MAO-A)と同様に、ドーパミンも分解する(ただし一部の研究ではこれに反する結果が得られており、MAO-Bはドーパミンを直接的には分解せず、GABAの合成を担っていることが示唆されている[6])。

構造と機能

編集MAO-Bの基質結合部位には2つの部分からなる疎水的で細長い形状のくぼみが存在し、「開いた」コンフォメーションではこのくぼみの総体積は700 Å3近くになる。一方、MAO-Aの基質結合部位のくぼみは1つの部分からなる丸い形状であり、体積はMAO-Bのものよりも大きい[7]。

MAO-Bの2つのくぼみはentrance cavity(約290 Å3)、substrate cavity(active site cavity、約390 Å3)と呼ばれており、Ile199の側鎖が両者の間でゲートとして機能している。基質または阻害剤の結合によって「開いた」または「閉じた」形状のいずれかの状態となり、このことが阻害剤のMAO-B特異性に重要であることが示されている。Substrate cavityの末端には補因子のFADが位置しており、aromatic cageと呼ばれる2つのほぼ平行なチロシン残基(398と435)とフラビンによってアミンの結合に適した部位が形成されている[7]。

MAO-Aと同様に、MAO-Bは一級アリールアルキルアミンに対する酸素依存的酸化反応を触媒する[8]。反応産物は対応するアルデヒド、過酸化水素、アンモニアである。

- Amine + O2 + H2O → Aldehyde + H2O2 + NH3

この反応は三段階で進行すると考えられている。まず、アミンが対応するイミンに酸化され、FADがFADH2へ還元される。続いて、酸素がFADH2から2つの電子と2つのプロトンを受容して過酸化水素が形成され、FADが再生される。最後に、イミンが水分子によって加水分解され、アンモニアとアルデヒドが形成される[7][9]。

MAO-Aとの差異

編集MAO-Aはチラミンの代謝に関与しているため、MAO-Aの阻害、特に不可逆的阻害は、チーズなどチラミンを多く含む食品を摂取した際に血清チラミン濃度の上昇による高血圧症状の原因となる場合がある(この作用は俗に「チーズ効果」("cheese effect")と呼ばれている)。MAO-Aはセロトニン、ノルアドレナリン、ドーパミンの代謝に関与し、MAO-Bは主にドーパミンを代謝する[10]。特定の疾患の治療に際しては両者の基質選択性の差異が利用され、MAO-A阻害薬はうつ病の治療に、そしてMAO-B阻害薬はパーキンソン病の治療に利用されるのが典型的である[11][12]。

疾患と老化における役割

編集アルツハイマー病とパーキンソン病は、どちらも脳内のMAO-B濃度の上昇と関連している[13][14]。MAO-Bの正常な活性は活性酸素種の形成をもたらし、細胞を直接的に傷害する[15]。MAO-B濃度は年齢とともに上昇することが示されており、加齢に伴う認知機能の低下や神経疾患の発症可能性の増大に関与していることが示唆される[16]。MAOB遺伝子の高活性型多型は負の情動性と関連しており、抑うつの根底因子として疑われている[17]。また、MAO-Bの活性はストレスによる心損傷にも関与していることが示されている[18][19]。脳内でのMAO-Bの過剰発現や濃度の上昇は、γ-セクレターゼを介した機構によってアミロイドβ(Aβ)の蓄積と関連している。γ-セクレターゼはアルツハイマー病やパーキンソン病の患者にみられるプラークの形成を担っている。siRNAによるMAO-BのサイレンシングやMAO-B選択的阻害薬(セレギリン、ラサギリン)による阻害は、脳内のAβプラークの減少といった、アルツハイマー病やパーキンソン病と関係した症状の進行の低下や改善をもたらす可能性がある[20][21]。

動物モデル

編集MAO-Bを産生することができないトランスジェニックマウスは、パーキンソン病モデルに対して抵抗性を示すことが示されている[22][23][24]。また、ストレスに対する応答性の増加(これはMAO-Aノックアウトマウスでもみられる)[25]やβ-フェネチルアミンの増加も示す[23][25]。さらに、行動の脱抑制や不安関連行動の低下もみられる[26]。

ラットでは、MAO-Bの阻害によって視神経変性など加齢と関連した多くの生物学的変化が防がれることが示されており、寿命も最大で39%伸長する[27][28]。

ヒトでの欠損の影響

編集MAOA遺伝子の欠損は境界知能と異常行動をもたらし、またMAOAとMAOBをともに欠損している場合には重度の知的障害となるのに対し、MAOBのみを欠損している場合には尿中フェネチルアミン濃度の上昇を除いて異常はみられない[29]。フェネチルアミンやその他の微量アミンの重要性を示す研究もあり、これらはアンフェタミンと同じ受容体TAAR1を介してカテコールアミンやセロトニンによる神経伝達を調節していることが知られている[30]。

健康な人物において自然な加齢を遅らせることを目的としたMAO-B阻害薬の予防的使用が提唱されているものの、依然として多くの議論のあるトピックである[31][32]。

選択的阻害剤

編集種依存的な多様性が阻害効力の外挿の障害となる場合がある[33]。

可逆的

編集天然物

編集合成化合物

編集- サフィナミドとそのアナログ[39]

- 5H-Indeno[1,2-c]pyridazin-5-ones[33][40][41]

- カルコン誘導体[42]

- 2-(N-Methyl-N-benzylaminomethyl)-1H-pyrrole[43]

- 1-(4-Arylthiazol-2-yl)-2-(3-methylcyclohexylidene)hydrazine[44]

- 2-チアゾリルヒドラゾン[45]

- 3,5-ジアリールピラゾール[46]

- ピラゾリン誘導体[47][48]

- いくつかのクマリン誘導体[49][33]

- フェニルクマリンとそのアナログ[50][51][52][53]

- クロモン-3-フェニルカルボキサミド[54]

- イサチン[55]

- フタルイミド[56]

- 8-ベンジルオキシカフェイン[57][58]および8-(3-クロロスチリル)カフェインアナログ[59]

- (E,E)-8-(4-phenylbutadien-1-yl)caffeines(A2A受容体に対するアンタゴニスト作用も有する)[60]

- インダゾール-5-カルボキサミドおよびインドール-5-カルボキサミド[61]

不可逆的(共有結合)

編集出典

編集- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000069535 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000040147 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Entrez Gene: MAOB monoamine oxidase B”. 2023年12月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Redefining differential roles of MAO-A in dopamine degradation and MAO-B in tonic GABA synthesis”. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 53 (7): 1148–1158. (July 2021). doi:10.1038/s12276-021-00646-3. PMC 8333267. PMID 34244591.

- ^ a b c “Structural insights into the mechanism of amine oxidation by monoamine oxidases A and B”. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 464 (2): 269–76. (August 2007). doi:10.1016/j.abb.2007.05.006. PMC 1993809. PMID 17573034.

- ^ “Crystal structures of monoamine oxidase B in complex with four inhibitors of the N-propargylaminoindan class”. J. Med. Chem. 47 (7): 1767–74. (March 2004). doi:10.1021/jm031087c. PMID 15027868.

- ^ “Structure-function relationships in flavoenzyme-dependent amine oxidations: A comparison of polyamine oxidase and monoamine oxidase”. Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (27): 23973–23976. (July 5, 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.R200005200. PMID 12015330.

- ^ “Therapeutic applications of selective and non-selective inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A and B that do not cause significant tyramine potentiation”. Neurotoxicology 25 (1–2): 243–50. (January 2004). doi:10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00103-7. PMID 14697899.

- ^ “Reversible monoamine oxidase-A inhibitors in resistant major depression”. Clin Neuropharmacol 16 (Suppl 2): S69–76. (1993). PMID 8313400.

- ^ “MAO-inhibitors in Parkinson's Disease”. Exp Neurobiol 20 (1): 1–17. (March 2011). doi:10.5607/en.2011.20.1.1. PMC 3213739. PMID 22110357.

- ^ “Increased monoamine oxidase B activity in plaque-associated astrocytes of Alzheimer brains revealed by quantitative enzyme radioautography”. Neuroscience 62 (1): 15–30. (September 1994). doi:10.1016/0306-4522(94)90311-5. PMID 7816197.

- ^ “Metabolic control analysis in a cellular model of elevated MAO-B: relevance to Parkinson's disease”. Neurotox Res 16 (3): 186–93. (October 2009). doi:10.1007/s12640-009-9032-2. PMC 2727365. PMID 19526285.

- ^ “Molecular mechanism of the relation of monoamine oxidase B and its inhibitors to Parkinson's disease: Possible implications of glial cells”. Oxidative Stress and Neuroprotection. Journal of Neural Transmission. Supplementa. 71. (2006). 53–65. doi:10.1007/978-3-211-33328-0_7. ISBN 978-3-211-33327-3. PMID 17447416

- ^ “Perspectives on MAO-B in aging and neurological disease: where do we go from here?”. Mol. Neurobiol. 30 (1): 77–89. (August 2004). doi:10.1385/MN:30:1:077. PMID 15247489.

- ^ “Negative emotionality: monoamine oxidase B gene variants modulate personality traits in healthy humans”. J Neural Transm 116 (10): 1323–34. (October 2009). doi:10.1007/s00702-009-0281-2. PMC 3653168. PMID 19657584.

- ^ “Monoamine oxidases (MAO) in the pathogenesis of heart failure and ischemia/reperfusion injury”. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813 (7): 1323–32. (July 2011). doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.09.010. PMC 3030628. PMID 20869994.

- ^ “Monoamine oxidase B prompts mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunction in pressure overloaded hearts”. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20 (2): 267–80. (January 2014). doi:10.1089/ars.2012.4616. PMC 3887464. PMID 23581564.

- ^ “Monoamine oxidase B is elevated in Alzheimer disease neurons, is associated with γ-secretase and regulates neuronal amyloid β-peptide levels”. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy 9 (1): 57. (August 2017). doi:10.1186/s13195-017-0279-1. PMC 5540560. PMID 28764767.

- ^ “Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: promising therapeutic agents for Alzheimer's disease (Review)”. Molecular Medicine Reports 9 (5): 1533–41. (May 2014). doi:10.3892/mmr.2014.2040. PMID 24626484.

- ^ “MAO-A and -B gene knock-out mice exhibit distinctly different behavior”. Neurobiology (Bp) 7 (2): 235–46. (1999). PMID 10591056.

- ^ a b “Increased stress response and beta-phenylethylamine in MAOB-deficient mice.”. Nature Genetics 17 (2): 206–10. (October 1997). doi:10.1038/ng1097-206. PMID 9326944.

- ^ “Monoamine oxidase: from genes to behavior.”. Annual Review of Neuroscience 22: 197–217. (1999). doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.197. PMC 2844879. PMID 10202537.

- ^ a b “Cloning, after cloning, knock-out mice, and physiological functions of MAO A and B.”. Neurotoxicology 25 (1–2): 21–30. (January 2004). doi:10.1016/s0161-813x(03)00112-8. PMID 14697877.

- ^ “Behavioral disinhibition and reduced anxiety-like behaviors in monoamine oxidase B-deficient mice.”. Neuropsychopharmacology 34 (13): 2746–57. (December 2009). doi:10.1038/npp.2009.118. PMC 2783894. PMID 19710633.

- ^ “Monoamine oxidase enzymes and oxidative stress in the rat optic nerve: age-related changes”. International Journal of Experimental Pathology 93 (6): 401–5. (December 2012). doi:10.1111/j.1365-2613.2012.00832.x. PMC 3521895. PMID 23082958.

- ^ “Chronic treatment of (-)deprenyl prolongs the life span of male Fischer 344 rats. Further evidence”. Life Sci. 52 (3): 281–8. (1993). doi:10.1016/0024-3205(93)90219-S. PMID 8423709.

- ^ “Specific genetic deficiencies of the A and B isoenzymes of monoamine oxidase are characterized by distinct neurochemical and clinical phenotypes”. J. Clin. Invest. 97 (4): 1010–9. (February 1996). doi:10.1172/JCI118492. PMC 507147. PMID 8613523.

- ^ “The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity”. J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–176. (January 2011). doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ “[Slowing the age-induced decline of brain function with prophylactic use of (−)-deprenyl (Selegiline, Jumex). Current international view and conclusions 25 years after the Knoll's proposal]” (ハンガリー語). Neuropsychopharmacol Hung 11 (4): 217–25. (December 2009). PMID 20150659.

- ^ “Antiaging treatments have been legally prescribed for approximately thirty years”. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1019 (1): 64–9. (June 2004). Bibcode: 2004NYASA1019...64U. doi:10.1196/annals.1297.014. PMID 15246996.

- ^ a b c “Impact of species-dependent differences on screening, design, and development of MAO B inhibitors”. J. Med. Chem. 49 (21): 6264–72. (October 2006). doi:10.1021/jm060441e. PMID 17034132.

- ^ “Natural and synthetic geiparvarins are strong and selective MAO-B inhibitors. Synthesis and SAR studies”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 12 (24): 3551–5. (December 2002). doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(02)00798-9. PMID 12443774.

- ^ “Inhibition of platelet MAO-B by kava pyrone-enriched extract from Piper methysticum Forster (kava-kava)”. Pharmacopsychiatry 31 (5): 187–92. (September 1998). doi:10.1055/s-2007-979325. PMID 9832350.

- ^ Hou, Wen-Chi; Lin, Rong-Dih; Chen, Cheng-Tang; Lee, Mei-Hsien (2005-08-22). “Monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibition by active principles from Uncaria rhynchophylla”. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 100 (1-2): 216–220. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.03.017. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 15890481.

- ^ “Evidences for the involvement of monoaminergic and GABAergic systems in antidepressant-like activity of garlic extract in mice”. Indian Journal of Pharmacology 40 (4): 175–179. (August 2008). doi:10.4103/0253-7613.43165. PMC 2792615. PMID 20040952.

- ^ “Monoamine oxidase inhibition by Rhodiola rosea L. roots”. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 122 (2): 397–401. (March 2009). doi:10.1016/j.jep.2009.01.007. PMID 19168123.

- ^ “Solid-phase synthesis and insights into structure-activity relationships of safinamide analogues as potent and selective inhibitors of type B monoamine oxidase”. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 50 (20): 4909–16. (October 2007). doi:10.1021/jm070725e. PMID 17824599.

- ^ compound #2d, “Synthesis, structural reassignment, and biological activity of type B MAO inhibitors based on the 5H-indeno[1,2-c]pyridazin-5-one core”. J. Med. Chem. 49 (12): 3743–7. (June 2006). doi:10.1021/jm051091j. PMID 16759116.

- ^ “Synthesis and monoamine oxidase inhibitory activity of new pyridazine-, pyrimidine- and 1,2,4-triazine-containing tricyclic derivatives”. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 50 (22): 5364–71. (November 2007). doi:10.1021/jm070728r. PMID 17910428.

- ^ “Chalcones: a valid scaffold for monoamine oxidases inhibitors”. J. Med. Chem. 52 (9): 2818–24. (May 2009). doi:10.1021/jm801590u. PMID 19378991.

- ^ compound #21, “Simple, potent, and selective pyrrole inhibitors of monoamine oxidase types A and B”. J. Med. Chem. 46 (6): 917–20. (March 2003). doi:10.1021/jm0256124. PMID 12620068.

- ^ compound # (R)-8b, “Synthesis, stereochemical separation, and biological evaluation of selective inhibitors of human MAO-B: 1-(4-arylthiazol-2-yl)-2-(3-methylcyclohexylidene)hydrazines”. J. Med. Chem. 53 (17): 6516–20. (September 2010). doi:10.1021/jm100120s. hdl:11573/360702. PMID 20715818.

- ^ compound #18, “Selective inhibitory activity against MAO and molecular modeling studies of 2-thiazolylhydrazone derivatives”. J. Med. Chem. 50 (4): 707–12. (February 2007). doi:10.1021/jm060869d. hdl:11573/231039. PMID 17253676.

- ^ compound #3g, “Monoamine oxidase isoform-dependent tautomeric influence in the recognition of 3,5-diaryl pyrazole inhibitors”. J. Med. Chem. 50 (3): 425–8. (February 2007). doi:10.1021/jm060868l. PMID 17266193.

- ^ compound #(S)-1, “Synthesis, molecular modeling studies, and selective inhibitory activity against monoamine oxidase of 1-thiocarbamoyl-3,5-diaryl-4,5-dihydro-(1H)- pyrazole derivatives”. J. Med. Chem. 48 (23): 7113–22. (November 2005). doi:10.1021/jm040903t. PMID 16279769.

- ^ “Development of selective and reversible pyrazoline based MAO-B inhibitors: virtual screening, synthesis and biological evaluation”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 21 (7): 1969–73. (April 2011). doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.02.030. PMID 21377879.

- ^ compound #41, “Structural insights into monoamine oxidase inhibitory potency and selectivity of 7-substituted coumarins from ligand- and target-based approaches”. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 49 (16): 4912–25. (2006). doi:10.1021/jm060183l. PMID 16884303.

- ^ compound #2, “MAO inhibitory activity modulation: 3-Phenylcoumarins versus 3-benzoylcoumarins”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 21 (14): 4224–7. (July 2011). doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.05.074. PMID 21684743.

- ^ “New halogenated 3-phenylcoumarins as potent and selective MAO-B inhibitors”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20 (17): 5157–60. (September 2010). doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.07.013. PMID 20659799.

- ^ “Synthesis and evaluation of 6-methyl-3-phenylcoumarins as potent and selective MAO-B inhibitors”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19 (17): 5053–5. (September 2009). doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.07.039. PMID 19628387.

- ^ “A new series of 3-phenylcoumarins as potent and selective MAO-B inhibitors”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19 (12): 3268–70. (June 2009). doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.085. PMID 19423346.

- ^ compound #9, #12, “Chromone 3-phenylcarboxamides as potent and selective MAO-B inhibitors”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 21 (2): 707–9. (January 2011). doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.11.128. PMID 21194943.

- ^ compound #9i, “Inhibition of monoamine oxidase by selected C5- and C6-substituted isatin analogues”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19 (1): 261–74. (January 2011). doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2010.11.028. PMID 21134756.

- ^ compound #5c, “Inhibition of monoamine oxidase by C5-substituted phthalimide analogues”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19 (16): 4829–40. (August 2011). doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.070. PMID 21778064.

- ^ “8-Aryl- and alkyloxycaffeine analogues as inhibitors of monoamine oxidase”. Eur J Med Chem 46 (8): 3474–85. (August 2011). doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.05.014. PMID 21621312.

- ^ “Inhibition of monoamine oxidase by 8-benzyloxycaffeine analogues”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18 (3): 1018–28. (February 2010). doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2009.12.064. PMID 20093036.

- ^ “Inhibition of monoamine oxidase B by analogues of the adenosine A2A receptor antagonist (E)-8-(3-chlorostyryl)caffeine (CSC)”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14 (10): 3512–21. (May 2006). doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.01.011. PMID 16442801.

- ^ “Dual inhibition of monoamine oxidase B and antagonism of the adenosine A(2A) receptor by (E,E)-8-(4-phenylbutadien-1-yl)caffeine analogues”. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 16 (18): 8676–84. (September 2008). doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.07.088. PMID 18723354.

- ^ “Indazole- and indole-5-carboxamides: selective and reversible monoamine oxidase B inhibitors with subnanomolar potency”. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 57 (15): 6679–6703. (August 2014). doi:10.1021/jm500729a. PMID 24955776.

関連項目

編集- モノアミン酸化酵素A(MAO-A)