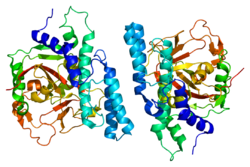

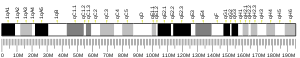

PARP1

PARP1(poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1)は、ヒトではPARP1遺伝子にコードされる酵素である[5]。NAD+ ADP-ribosyltransferase 1、poly[ADP-ribose] synthase 1などの名称でも知られる。 PARPファミリーの酵素の中で最も豊富に存在し、このファミリーに利用されるNAD+のうち90%をPARP1が占める[6]。PARP1は大部分が細胞核に存在するが、一部は細胞質基質に存在することも報告されている[7]。

機能

編集PARP1はNAD+を用いてポリADPリボース(PAR)を合成し、タンパク質に転移する(ADPリボシル化)[8]。PARP1はDNA損傷の修復の他、炎症の誘導[9]や1型糖尿病の病理[10]にも関係している。また、PARP1は胃がんの発生ならびに増殖時にピロリ菌Helicobacter pyloriによって活性化される[11]。

DNA損傷修復における役割

編集PARP1はDNA損傷を検知する最初の応答因子の1つとして作用し、修復経路の選択を補助する[12]。PARP1はヒストンのADPリボシル化によるクロマチン構造の脱凝縮や、複数のDNA修復因子との相互作用や修飾によって修復の効率化に寄与する[6]。PARP1は、ヌクレオチド除去修復、非相同末端結合、マイクロホモロジー媒介末端結合、相同組換え修復、DNAミスマッチ修復など、いくつかのDNA修復経路の調節に関与することが示唆されている[12]。

PARP1は一本鎖DNA切断の修復に関与している。siRNAによるPARP1のノックダウンや低分子によるPARP1活性の阻害によって、一本鎖切断の修復は低下する。PARP1が存在しない場合、DNA複製の過程で複製フォークがこうした切断に遭遇することで複製フォークは停止し、その結果、二本鎖切断が蓄積する。こうした二本鎖切断は相同組換えを介して修復される。そのため、PARP1を欠く細胞はhyper-recombinagenic表現型(相同組換え頻度の増加など)を示し[13][14][15]、このことはマウスにおいてin vivoでもpunアッセイによって観察されている[16]。相同組換えが正常に機能している場合には、PARP1ヌル変異体(機能的なPARP1が存在しない細胞)は不健康な表現型を示さず、PARP1ノックアウトマウスでも不利な表現型や腫瘍形成の増加などは全く見られない[17]。

炎症における役割

編集PARP1は、NF-κBによるTNFやIL-6、iNOSなど炎症性メディエーターの転写に必要である[9][18]。PARP1の活性は多くの組織で年齢とともに増加する炎症性マクロファージに寄与する[19]。PARP1によるHMGB1のADPリボシル化はアポトーシスを起こした細胞の除去を阻害し、それによって炎症を維持する[20]。

喘息においては、PARP1はCD4+T細胞、好酸球、樹状細胞などの免疫細胞のリクルートと機能を促進する[18]。

がんにおける過剰発現

編集PARP1はエラーが生じやすいDNA修復経路であるマイクロホモロジー媒介末端結合(MMEJ)に必要な6つの酵素のうちの1つである[21]。MMEJは、欠失、転座、逆位やその他の複雑な再配置などの染色体異常と高頻度で関係している。PARP1がアップレギュレーションされている場合にはMMEJが増加し、ゲノム不安定性が引き起こされる[22]。PARP1のアップレギュレーションとMMEJの増加はチロシンキナーゼ活性化型の白血病でみられる[22]。

PARP1はプロモーターのETS結合部位がエピジェネティックに低メチル化状態となっているときにも過剰発現し、子宮体がん[23]、BRCA(BRCA1/2)変異型卵巣がん[24]、BRCA変異型漿液性卵巣がん[25]のプログレッションに寄与している。

PARP1は他にも神経芽腫[26]、HPV関連中咽頭がん[27]、精巣やその他の生殖細胞の腫瘍[28]、ユーイング肉腫[29]、悪性リンパ腫[30]、乳がん[31]、結腸がん[32]など多数のがんで過剰発現している。

がん治療への応用

編集PARP阻害薬のがん治療における有効性の試験が行われている[33]。PARP1阻害薬はBRCAness(BRCA遺伝子に変異がないにもかかわらず相同組換え修復異常がみられる状態)のがんに対して非常に有効な治療となる可能性があると考えられている。こうした腫瘍はPARP阻害薬に対する感受性が高い一方で、BRCA相同組換え経路が機能している健康な細胞に対しては有害な影響が及ばないためである。このことは、すべての細胞に対して毒性が高く、健康な細胞にDNA損傷を誘導して二次性のがんの形成をもたらす可能性がある従来型の化学療法とは対照的である[34][35]。

老化

編集13種の哺乳類(ラット、モルモット、ウサギ、マーモセット、ヒツジ、ブタ、ウシ、ボノボ、ウシ、ロバ、ゴリラ、ゾウ、ヒト)の透過処理された単核白血球でPARP活性(主にPARP1によるもの)が測定されており、その活性はその種の最長寿命と相関していることが示されている[36]。センテナリアン(100歳以上の高齢者)の血液試料から樹立されたリンパ芽球細胞株は、より若い(20歳から70歳)個人の試料に由来する細胞株よりも有意に高いPARP活性を示す[37]。ヒトの早老疾患であるウェルナー症候群ではWRNタンパク質に欠陥がみられるが、PARP1とWRNはDNA切断のプロセシングに関与する複合体の一部を構成している[38]。こうした事実は、長寿とPARPを介したDNA修復能力との関連を示唆している。さらに、PARPは活性酸素種の産生に対抗する作用を示し、DNAやタンパク質に対する酸化損傷を阻害することで長寿に寄与している可能性がある[39]。

レスベラトロールはチロシルtRNAシンテターゼ(TyrRS)との相互作用を介して、PARP1を主要な機能標的としているようである[40]。TyrRSはストレス条件下で核内へ移行して、PARP1のNAD+依存的なポリADPリボシル化を刺激する。その結果、PARP1はクロマチンの構造タンパク質からDNA損傷応答因子、転写調節因子へと機能が変化する[41]。

PARP1のmRNAとタンパク質のレベルは転写因子ETS1の発現レベルによって部分的に制御されており、EST1はPARP1のプロモーター領域の複数のETS1結合部位と相互作用する[42]。ETS1がPARP1のプロモーターにどの程度結合するかは、ETS1結合部位のCpGアイランドのメチル化状態に依存している[23]。ETS1結合部位のCpGアイランドがエピジェネティックに低メチル化状態となっている場合には、PARP1の発現レベルが高くなる[23][24]。

高齢者(69歳から75歳)由来の細胞では、PARP1とPARP2の恒常的発現レベルは若年成人(19歳から26歳)と比較して半分程度にまで低下している。しかしながら、センテナリアン(100歳から107歳)では、PARP1の恒常的発現レベルは若年と同等である[43]。センテナリアンでみられるPARP1の高レベル発現は、過酸化水素による亜致死性のDNA酸化損傷に対する効率的な修復を可能にしていることが示されている[43]。センテナリアンでみられるPARP1の高レベルの恒常的発現は、エピジェネティックな発現制御の変化によるものであると考えられている[43]。

植物のPARP1

編集植物にも動物のPARP1とかなり類似したPARP1が存在し、DNA損傷、感染やその他のストレスに対する応答時のポリADPリボシル化の役割の研究が行われている[44][45]。興味深いことに、シロイヌナズナArabidopsis thalianaでは(そしておそらく他の植物でも)、DNA損傷や病原性細菌に対する防御応答においてPARP1よりもPARP2がより大きな役割を果たしている[46]。植物のPARP2の調節ドメインと触媒ドメインにはPARP1と中程度の類似性しか存在せず、また植物や動物のPARP1にはジンクフィンガー型DNA結合モチーフが存在するのに対し、PARP2のN末端にはSAP DNA結合モチーフが存在する[46]。

相互作用

編集PARP1は次に挙げる因子と相互作用することが示されている。

出典

編集- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000143799 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000026496 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in the nervous system”. Neurobiology of Disease 7 (4): 225–39. (August 2000). doi:10.1006/nbdi.2000.0324. PMID 10964595.

- ^ a b “NAD + metabolism: pathophysiologic mechanisms and therapeutic potential”. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 5 (1): 227. (2020). doi:10.1038/s41392-020-00311-7. PMC 7539288. PMID 33028824.

- ^ Karpińska, Aneta. “Quantitative analysis of biochemical processes in living cells at a single-molecule level: a case of olaparib–PARP1 (DNA repair protein) interactions”. Analyst. doi:10.1039/D1AN01769A. PMID 34726203.

- ^ Nilov, DK; Pushkarev, SV; Gushchina, IV; Manasaryan, GA; Kirsanov, KI; Švedas, VK (2020). “Modeling of the enzyme-substrate complexes of human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1”. Biochemistry (Moscow) 85 (1): 99–107. doi:10.1134/S0006297920010095. PMID 32079521.

- ^ a b “Pleiotropic cellular functions of PARP1 in longevity and aging: genome maintenance meets inflammation”. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2012: 321653. (2012). doi:10.1155/2012/321653. PMC 3459245. PMID 23050038.

- ^ “Entrez Gene: PARP1 poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase family, member 1”. 2022年5月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Activation of the abundant nuclear factor poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 by Helicobacter pylori”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (47): 19998–20003. (November 2009). Bibcode: 2009PNAS..10619998N. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906753106. PMC 2785281. PMID 19897724.

- “Team finds link between stomach-cancer bug and cancer-promoting factor”. Medical Xpress (January 6, 2010). 2022年5月7日閲覧。

- ^ a b “The comings and goings of PARP-1 in response to DNA damage”. DNA Repair 71: 177–182. (November 2018). doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2018.08.022. PMC 6637744. PMID 30177435.

- ^ “PARP inhibition versus PARP-1 silencing: different outcomes in terms of single-strand break repair and radiation susceptibility”. Nucleic Acids Research 36 (13): 4454–64. (August 2008). doi:10.1093/nar/gkn403. PMC 2490739. PMID 18603595.

- ^ “Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP-1) has a controlling role in homologous recombination”. Nucleic Acids Research 31 (17): 4959–64. (September 2003). doi:10.1093/nar/gkg703. PMC 212803. PMID 12930944.

- ^ “Stimulation of intrachromosomal homologous recombination in mammalian cells by an inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribosylation)”. Nucleic Acids Research 19 (21): 5943–7. (November 1991). doi:10.1093/nar/19.21.5943. PMC 329051. PMID 1945881.

- ^ “PARP1 suppresses homologous recombination events in mice in vivo”. Nucleic Acids Research 38 (21): 7538–45. (November 2010). doi:10.1093/nar/gkq624. PMC 2995050. PMID 20660013.

- ^ “Mice lacking ADPRT and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation develop normally but are susceptible to skin disease”. Genes & Development 9 (5): 509–20. (March 1995). doi:10.1101/gad.9.5.509. PMID 7698643.

- ^ a b “Poly(ADP-Ribose)Polymerase-1 in Lung Inflammatory Disorders: A Review”. Frontiers in Immunology 8: 1172. (2017). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01172. PMC 5610677. PMID 28974953.

- ^ “Macrophage Immunometabolism and Inflammaging: Roles of Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Cellular Senescence, CD38, and NAD”. Immunometabolism 2 (3): e200026. (2020). doi:10.20900/immunometab20200026. PMC 7409778. PMID 32774895.

- ^ “Multifaceted Role of PARP-1 in DNA Repair and Inflammation: Pathological and Therapeutic Implications in Cancer and Non-Cancer Diseases”. Cells 9 (1): 41. (2019). doi:10.3390/cells9010041. PMC 7017201. PMID 31877876.

- ^ “Homology and enzymatic requirements of microhomology-dependent alternative end joining”. Cell Death & Disease 6 (3): e1697. (March 2015). doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.58. PMC 4385936. PMID 25789972.

- ^ a b “c-MYC Generates Repair Errors via Increased Transcription of Alternative-NHEJ Factors, LIG3 and PARP1, in Tyrosine Kinase-Activated Leukemias”. Molecular Cancer Research 13 (4): 699–712. (April 2015). doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0422. PMC 4398615. PMID 25828893.

- ^ a b c “Hypomethylation of ETS transcription factor binding sites and upregulation of PARP1 expression in endometrial cancer”. BioMed Research International 2013: 946268. (2013). doi:10.1155/2013/946268. PMC 3666359. PMID 23762867.

- ^ a b “Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 transcriptional regulation: a novel crosstalk between histone modification H3K9ac and ETS1 motif hypomethylation in BRCA1-mutated ovarian cancer”. Oncotarget 5 (1): 291–7. (January 2014). doi:10.18632/oncotarget.1549. PMC 3960209. PMID 24448423.

- ^ “Promoter hypomethylation, especially around the E26 transformation-specific motif, and increased expression of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 in BRCA-mutated serous ovarian cancer”. BMC Cance 13: 90. (February 2013). doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-90. PMC 3599366. PMID 23442605.

- ^ “Alternative NHEJ Pathway Components Are Therapeutic Targets in High-Risk Neuroblastoma”. Molecular Cancer Research 13 (3): 470–82. (March 2015). doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0337. PMID 25563294.

- ^ “Subjugation of TGFβ Signaling by Human Papilloma Virus in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Shifts DNA Repair from Homologous Recombination to Alternative End Joining”. Clinical Cancer Research 24 (23): 6001–6014. (December 2018). doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1346. PMID 30087144.

- ^ “PARP expression in germ cell tumours”. Journal of Clinical Pathology 66 (7): 607–12. (July 2013). doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2012-201088. PMID 23486608.

- ^ “Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase turnover alterations do not contribute to PARP overexpression in Ewing's sarcoma cells”. Oncology Reports 9 (3): 529–32. (2002). doi:10.3892/or.9.3.529. PMID 11956622.

- ^ “Enhanced expression of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase gene in malignant lymphoma”. American Journal of Hematology 37 (4): 223–7. (August 1991). doi:10.1002/ajh.2830370402. PMID 1907096.

- ^ “Nuclear PARP-1 protein overexpression is associated with poor overall survival in early breast cancer”. Annals of Oncology 23 (5): 1156–64. (May 2012). doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr361. PMID 21908496.

- ^ “PARP-1 expression is increased in colon adenoma and carcinoma and correlates with OGG1”. PLOS ONE 9 (12): e115558. (2014). Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9k5558D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115558. PMC 4272268. PMID 25526641.

- ^ “Therapeutic Potential of NAD-Boosting Molecules: The In Vivo Evidence”. Cell Metabolism 27 (3): 529–547. (2018). doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.02.011. PMC 6342515. PMID 29514064.

- ^ “Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase”. Nature 434 (7035): 913–7. (April 2005). Bibcode: 2005Natur.434..913B. doi:10.1038/nature03443. PMID 15829966.

- ^ “Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy”. Nature 434 (7035): 917–21. (April 2005). Bibcode: 2005Natur.434..917F. doi:10.1038/nature03445. PMID 15829967.

- ^ “Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity in mononuclear leukocytes of 13 mammalian species correlates with species-specific life span”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 89 (24): 11759–63. (December 1992). Bibcode: 1992PNAS...8911759G. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.24.11759. PMC 50636. PMID 1465394.

- ^ “Increased poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity in lymphoblastoid cell lines from centenarians”. Journal of Molecular Medicine 76 (5): 346–54. (April 1998). doi:10.1007/s001090050226. PMID 9587069.

- ^ “Genetic cooperation between the Werner syndrome protein and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in preventing chromatid breaks, complex chromosomal rearrangements, and cancer in mice”. The American Journal of Pathology 162 (5): 1559–69. (May 2003). doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64290-3. PMC 1851180. PMID 12707040.

- ^ “PARP-1 inhibition with or without ionizing radiation confers reactive oxygen species-mediated cytotoxicity preferentially to cancer cells with mutant TP53”. Oncogene 37 (21): 2793–2805. (May 2018). doi:10.1038/s41388-018-0130-6. PMC 5970015. PMID 29511347.

- ^ “A human tRNA synthetase is a potent PARP1-activating effector target for resveratrol”. Nature 519 (7543): 370–3. (March 2015). Bibcode: 2015Natur.519..370S. doi:10.1038/nature14028. PMC 4368482. PMID 25533949.

- ^ “Automodification switches PARP-1 function from chromatin architectural protein to histone chaperone”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (35): 12752–7. (September 2014). Bibcode: 2014PNAS..11112752M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1405005111. PMC 4156740. PMID 25136112.

- ^ “Regulation of the human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase promoter by the ETS transcription factor”. Oncogene 18 (27): 3954–62. (July 1999). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202778. PMID 10435618.

- ^ a b c “Oxidative DNA damage repair and parp 1 and parp 2 expression in Epstein-Barr virus-immortalized B lymphocyte cells from young subjects, old subjects, and centenarians”. Rejuvenation Research 10 (2): 191–204. (June 2007). doi:10.1089/rej.2006.0514. PMID 17518695.

- ^ “Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in plants”. Trends in Plant Science 16 (7): 372–80. (July 2011). doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.008. PMID 21482174.

- ^ “Protein ADP-Ribosylation Takes Control in Plant-Bacterium Interactions”. PLOS Pathogens 12 (12): e1005941. (December 2016). doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005941. PMC 5131896. PMID 27907213.

- ^ a b “PARP2 Is the Predominant Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase in Arabidopsis DNA Damage and Immune Responses”. PLOS Genetics 11 (5): e1005200. (May 2015). doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005200. PMC 4423837. PMID 25950582.

- ^ a b c “Aprataxin, a novel protein that protects against genotoxic stress”. Human Molecular Genetics 13 (10): 1081–93. (May 2004). doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh122. PMID 15044383.

- ^ “Regulation of protein synthesis in heart muscle. II. Effect of amino acid levels and insulin on ribosomal aggregation”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 246 (7): 2163–70. (April 1971). doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)77203-2. PMID 5555565.

- ^ “Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is a B-MYB coactivator”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (14): 10692–6. (April 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.275.14.10692. PMID 10744766.

- ^ “The enzymatic and DNA binding activity of PARP-1 are not required for NF-kappa B coactivator function”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (49): 45588–97. (December 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M106528200. PMID 11590148.

- ^ “Poly(ADP-ribose) binds to specific domains of p53 and alters its DNA binding functions”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (19): 11839–43. (May 1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.19.11839. PMID 9565608.

- ^ a b “Functional association of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase with DNA polymerase alpha-primase complex: a link between DNA strand break detection and DNA replication”. Nucleic Acids Research 26 (8): 1891–8. (April 1998). doi:10.1093/nar/26.8.1891. PMC 147507. PMID 9518481.

- ^ “XRCC1 is specifically associated with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and negatively regulates its activity following DNA damage”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 18 (6): 3563–71. (June 1998). doi:10.1128/MCB.18.6.3563. PMC 108937. PMID 9584196.

- ^ “Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 interacts with OAZ and regulates BMP-target genes”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 311 (3): 702–7. (November 2003). doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.053. PMID 14623329.

関連文献

編集- “Beyond DNA repair, the immunological role of PARP-1 and its siblings”. Immunology 139 (4): 428–37. (August 2013). doi:10.1111/imm.12099. PMC 3719060. PMID 23489378. Review of the subject.

関連項目

編集- 老化のDNA損傷理論

- 最長寿命

- オラパリブ – PARP阻害薬

- PARP阻害薬

- パータナトス

- ポリ(ADP-リボース)ポリメラーゼ

- 老化