ニュージーランドバト

この記事は英語版の対応するページを翻訳することにより充実させることができます。(2021年12月) 翻訳前に重要な指示を読むには右にある[表示]をクリックしてください。

|

ニュージーランドバト Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae はハトの一種。ニュージーランドの固有種である。マオリ語ではkererū と呼ばれるが、ノースランド地方ではkūkupa ・kūkū などの名称でも呼ばれる。英名にはwood pigeonなどがあるが[2]、同じくwood pigeonの名で呼ばれるモリバト(北半球に分布)とは無関係である。

| ニュージーランドバト | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

カピティ島の個体

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 保全状況評価[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

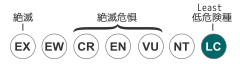

| LEAST CONCERN (IUCN Red List Ver.3.1 (2001))

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 分類 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 学名 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae (Gmelin, 1789) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 英名 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| New Zealand pigeon Kererū |

東南アジア・アフリカ・ニュージーランドに広く分布するアオバト亜科に属する。この亜科は果実、特に液果を主食とすることが特徴である[3]。ニュージーランドバト属 Hemiphaga はニュージーランド周辺とノーフォーク島に固有であるが、ラウル島からも本属に属する14世紀頃の骨が出土している[4]。

形態

編集51cm・650gと大型の鳥だが、チャタム諸島の個体(後に別種とされた)はさらに大きく、55cm・800gに達する[5]。頭部から胸部、翼は紫の光沢のある緑色。胸の下側は白い。嘴と脚は赤[6]。

分類

編集一般的には、基亜種を含め3亜種を認める。その内H. n. spadicea (w:Norfolk pigeon) は現在では絶滅しているが、羽の色や形態的特徴が異なっていた[7]。

もう一つの亜種H. n. chathamensis はチャタム諸島に生息する亜種であるが、2001年にHemiphaga chathamensis として分離された[8]。

生態

編集ノースランド地方からスチュアート島まで広い範囲分布域を持ち、沿岸から山地まで様々な森林で見られた[9]。

摂餌

編集一般的には果食性である。ニュージーランドの鳥としては、直径1cmを超える大きな果実を丸ごと消費できる唯一の種である。タライレのような在来植物の種子の拡散に関わるため、生態系の中でも重要な地位にある[10]。

果実があまり利用できない時季には葉も食べる。本種が最も好む葉は、移入種であるスモモ亜属の葉である[11]。

繁殖

編集繁殖は果実に依存しているが、季節や地域、果実の作況によってその利用可能量は変化する。特に北島北部では、他のアオバト類と同様、クスノキ科・ヤシ科のような熱帯由来の果実を利用するが[12][13][14][15]、ゴンドワナ大陸の遺存種であるマキ科のミロ Prumnopitys ferruginea やカヒカテア Dacrycarpus dacrydioides などの果実も利用する[13][14][15][16]。北島の北部は温暖であり十分な果実が利用できるため、換羽の時期にあたる3-5月を除いては周年繁殖する[10]。

樹上に、数本の小枝を束ねた簡易な巣を作り、1個の卵を産む。卵は28–29日で孵化し、雛はその後30-45日で巣立つ[17]。

保護

編集餌を巡る競争のあるフクロギツネやクマネズミのほか、オコジョやネコなどの外来種による被害を受けている[1]。

個体数は狩猟・生息地破壊・繁殖率の低下により減少している[17][18][19]。1860年代頃まで本種の個体数は非常に多く、結実した樹木に大きな群れで集まり、餌を食べていた[20]。狩猟規制は1864年から導入され、1921年には完全に保護されることが決定されたが[3]、狩猟規制は完全でない部分がある。マオリの中には、伝統的な権利として本種の狩猟権を主張するグループもある[21]。

関連項目

編集脚注

編集- ^ a b BirdLife International (2014). "Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ^ "Drunk kereru fall from trees", Feb 22, 2013, Laura Mills & Kurt Bayer, nzherald.co.nz

- ^ a b Falla, R. A., R. B. Sibson, and E. G. Turbott (1979). The new guide to the birds of New Zealand and outlying islands. Collins, Auckland.

- ^ Worthy, T. H., and R. Brassey. (2000). New Zealand pigeon (Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae) on Raoul Island, Kermadec Group. Notornis 47 (1): 36–38

- ^ Robertson, Hugh, and Barrie Heather. 1999. The Hand Guide to the Birds of New Zealand. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-19-850831-X

- ^ “Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae in Birdlife species”. 2015年2月2日閲覧。

- ^ James, R. E. (1995). Breeding ecology of the New Zealand pigeon at Wenderholm Regional Park. p93. School of Environmental and Marine Science. University of Auckland, Auckland.

- ^ Millener, P. R., and R. G. Powlesland. (2001). The Chatham Island pigeon (Chatham pigeon) deserves full species status; Hemiphaga chathamensis (Rothschild 1891); Aves: Columbidae. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 31:365–383.

- ^ Clout, M. N., P. D. Gaze, J. R. Hay, and B. J. Karl. (1986) Habitat use and spring movements of New Zealand pigeons at Lake Rotoroa, Nelson Lakes National Park. Notornis 33:37–44.

- ^ a b Christine Mander, Rod Hay and Ralph Powlesland. (1998) Monitoring and management of kereru (Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae), Department of Conservation technical series (ISSN 1172-6873), number 15. Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. ISBN 0-478-21751-X. Accessed 2008-01-13.

- ^ O'Donnel, C & P. Dilks (1994) "Foods and foraging of forest birds in temperate rainforest, South Westland, New Zealand" New Zealand Journal of Ecology 18(2): 87–107. [1]

- ^ Bell, R. (1996). Seed dispersal by kereru (Hemiphaga novaseelandiae) at Wenderholm Regional Park. p87. School of Biological Sciences. University of Auckland, Auckland.

- ^ a b Clout, M. N., and J. R. Hay. (1989) The importance of birds as browsers, pollinators and seed dispersers in New Zealand forests. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 12:27–33.

- ^ a b Clout, M. N., B. J. Karl, and P. D. Gaze. (1991). Seasonal movements of New Zealand pigeons from a lowland forest reserve. Notornis 38:37–47.

- ^ a b McEwen, W. M. 1978. The food of the New Zealand pigeon (Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae). New Zealand Journal of Ecology 1:99–108,

- ^ Clout, M. N., and J. A. V. Tilley. (1992) Germination of miro (Prumnopitys ferruginea) seeds after consumption by New Zealand pigeons (Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae). New Zealand Journal of Ecology 30:25–28.

- ^ a b Clout, M. N., K. Denyer, R. E. James, and I. G. Mcfadden. (1995) Breeding success of New Zealand pigeons (Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae) in relation to control of introduced mammals. New Zealand Journal of Ecology:209–212.

- ^ Clout, M. N., B. J. Karl, R. J. Pierce, and H. A. Robertson. (1995) Breeding and survival of New-Zealand pigeons Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae. Ibis 137:264–271.

- ^ Clout, M. N., and A. J. Saunders. (1995) Conservation and ecological restoration in New Zealand. Pacific Conservation Biology 2:91–98.

- ^ Best, E. (1977). Forest lore of the Maori. E.C. Keating Government Printer, Wellington, New Zealand.

- ^ Feldman, James W. (2001). "Enforcement, 1922–60", chapter 3 Treaty Rights and Pigeon Poaching: Alienation of Maori Access to Kereru, 1864–1960. Waitangi Tribunal, Wellington, New Zealand. ISBN 0-908810-55-5

参考文献

編集- Dijkgraaf, Astrid Cora. 2002. Phenology and frugivory of large-fruited species in northern New Zealand and the impacts of introduced mammals. PhD Thesis, School of Biological Sciences. University of Auckland, Auckland.

外部リンク

編集- Wood pigeon/kereru: New Zealand Native land birds from the Department of Conservation

- The Kereru Discovery Project, a programme for New Zealanders to help arrest the decline of the species through awareness and action in their own gardens

- Kereru, the New Zealand pigeon, Gallery of New Zealand Birds, New Zealand Birds Ltd