PZP

PZP(pregnancy zone protein)は、ヒトでは12番染色体のPZP遺伝子によってコードされるタンパク質である[5]。PAPはα2-マクログロブリン(α2M)ファミリーのタンパク質である[6]。多くの場合妊娠と関係しており、妊娠時には血漿タンパク質の中で最も多いものとなる場合もある[7]。PZPは妊娠時の免疫調節に関与すると考えられているが、その機構、機能、構造の多くの面が未解明である[8][9]。PZPはさまざまな疾患のバイオマーカーとなることが報告されており、近年の研究はPZP値の調節異常がどのようにマーカーとして機能するのかの解明に焦点が当てられている[10]。

| PZP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 識別子 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 記号 | PZP, CPAMD6, alpha-2-macroglobulin like, PZP alpha-2-macroglobulin like | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 外部ID | OMIM: 176420 MGI: 87854 HomoloGene: 74452 GeneCards: PZP | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| オルソログ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 種 | ヒト | マウス | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Entrez | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ensembl | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UniProt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (タンパク質) |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

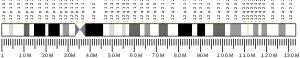

| 場所 (UCSC) | Chr 12: 9.15 – 9.21 Mb | Chr 12: 128.46 – 128.5 Mb | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PubMed検索 | [3] | [4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ウィキデータ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

発見

編集PZPが報告された最初の論文は1959年のO. Smithiesによるものである[11][12]。PZPはデンプンゲル分域電気泳動を用いた実験から発見され、妊娠後期と出産後の女性の10%の血清中でタンパク質のバンドが検出された[11][12][13]。数年後、タンパク質の検出法はJ. F. AfonsoとR. R. Alvarezによって改良された[11][14]。

命名

編集PZPはその発見以降、学術文献において、α2-pregnoglobulin、pregnancy-associated α2-glycoprotein、α-acute-phase glycoprotein、alpha-2-macroglobulin like、Xh-antigen、Schwangerschaftsprotein-3、Pα-1、pregnancy-associated α-macroglobulin、pregnancy-associated globulin、α2-PAGなど多数の名称で呼ばれてきた[9][15][16][17]。

遺伝子発現とタンパク質の局在

編集PZP遺伝子は36個のエクソンからなり、12番染色体の短腕p12-13に位置している[15]。PZP遺伝子にコードされるPZPタンパク質は1482アミノ酸からなる[18]。PZP遺伝子は子宮、肝臓、脳など多数の組織で発現している。PZPタンパク質は血漿、脳脊髄液、滑液中に検出される[15][19]。

健康な成人と小児では、PZPは男性と女性の双方で低レベルで存在している[20]。健康なヒトの血漿中のPZP濃度は0.03 mg/mL未満であるが、妊娠時の女性では0.5–3.0 mg/mLにまで上昇する[21]。

PZPの量に対する避妊薬の影響を観察した1976年の研究では、エストロゲンがPZPの発現の制御に部分的に寄与しているという推測がなされている[15][22]。避妊薬を用いた1971年の研究では、異なるタイプのピルによって異なるPZPの応答が誘導されることが記されており、ピルの成分が結果に与える影響については疑問視されている[23]。

タンパク質構造

編集PZPは、機能的活性を有する360 kDaのホモ二量体として存在する。この二量体化は180 kDaの単量体間のジスルフィド結合の形成によるものである。PZPは高度にグリコシル化された形で分泌される[24]。この構造は、変性させたPZPは360 kDaであり、その後の還元によって180 kDaのサブユニットとなることから実験的に確証された。180 kDaのサブユニットの一部は、切断されて90 kDaの断片となっていることが示されている[25][26]。

PZPの各サブユニットにはチオエステル基が存在し、シグナルドメイン、ベイト領域(bait region)、受容体結合ドメインが存在する[15][24]。ベイト領域には多数のプロテアーゼ切断部位が存在し、受容体結合ドメインには低密度リポタンパク質受容体関連タンパク質(LRP)が結合する[15]。ベイト領域の研究からは、この領域の6番目のバリンがメチオニンとなった稀な多型が存在することが示されている[27]。また、1180番のアミノ酸のプロリン/スレオニン多型、4097番の塩基のアデニン/グアニン多型も報告されている[24]。

PZPには多数のN-グリコシル化部位が存在し、Asn1430、Asn997、Asn932、Asn875、Asn753、Asn406、Asn392、Asn246、Asn69、Asn54のグリコシル化が記載されている[15]。PZPとα2Mの対応するアミノ酸配列の同一性は71%である[24]。

PZPの複数ドメインのフォールドに関する情報は限られており、その三次構造は変形後のα2Mの4.3 Å分解能の構造から推測されるのみである[15]。2018年11月の時点で、PZPの結晶構造はPDBに登録されていない。

PZPとその3つの誘導体に関してモノクローナル抗体を用いて行われた1988年の研究では、PZPとその誘導体には少なくとも3つのコンフォメーション状態が存在する可能性が示されている[28]。他の研究では、α2MとPZPの露出した疎水性表面の性質から、両者のコンフォメーション状態には大きな差異が存在することが示されている[29]。

生化学的活性と機能

編集長年にわたってPZPはプロテアーゼインヒビターに分類されてきたが、2016年の論文では、ヘルパーT細胞の調節因子または細胞外シャペロンとしての役割が示唆された。しかしながら、より一般的な観点からは、PZPの具体的な生物学的意義はいまだ明らかではない[15]。

PZPはα2Mと類似した役割を果たすことが早くから主張されているが、α2Mの方がより多くのプロテアーゼに対して阻害活性を示す[16]。これに対し、PZPとPAI-2は明確な構造的類似性は見られないものの機能的共通性がみられ、細胞外液で相乗的または相補的に機能する[15]。

妊娠時には、PZPとPP14(placental protein-14)が協働してTh1細胞の活性化を阻害している可能性がある。この場合、結果的に母親の免疫系が胎児を攻撃するのを防ぐこととなる[30]。PZPの免疫調節機能について示唆されている機構としては、PZPがIL-6、IL-2、TNF-αなどのリガンドを非共有結合的に隔離することなどが提唱されている[10]。なお、PZPの阻害活性はベイト領域などの多型の影響も受けるため、PZPのレベルと活性は直接相関しない可能性がある[27]。

PZPがキモトリプシン様酵素など細胞内のプロテアーゼ活性の制御に関与していることを支持する十分な証拠は得られていない[15]。PZPは二量体型のα2Mとともに炎症性サイトカインや誤ったフォールディングを行ったタンパク質の除去を補助していると考えられている[15][31]。PZPは四量体型α2Mと比較して高い疎水的相互作用性を持つため、ホルダーゼ型のシャペロンなどとしての機能が示唆されている[29][32]。

PZPと組織プラスミノーゲン活性化因子(t-PA)の間の相互作用はα2Mとt-PAの間の相互作用よりも速い。t-PAは血漿線溶系の主要なセリンプロテアーゼであるため、PZPは妊娠時の線溶系プロテアーゼの制御に関与している可能性がある[33]。

他の因子との結合

編集PZPと結合することが示されている高分子には、胎盤成長因子、グリコデリン、血管内皮細胞増殖因子など妊娠と関係したものが含まれる[19]。

低分子アミンまたはプロテアーゼとの相互作用によるチオエステル結合の切断の結果、PZPにはコンフォメーションの変化が生じる。こうして変形したPZPがプロテアーゼと複合体を形成し、LRPのリガンドとして作用する機構は未だ不明である[7]。

α2-マクログロブリンとの比較

編集α2MとPZPは類似した一次構造を持つことが示されており、この2つのタンパク質は進化的に関連していることが示唆される[13][24]。

1984年の研究では、当時シーケンシングされていたPZPの残基はα2Mのものと68%の同一性があることが示された。しかしながら、ベイト領域は両者で大きく異なることが示された[13]。一方、ジスルフィド結合を形成するシステイン残基はα2MとPZPの間で保存されていることが観察された。PZPとα2Mには共通の抗原決定基が存在することも示唆されている[24]。

機能的には、α2MとPZPはどちらもプロテアーゼインヒビターとしての作用を示す。しかしながら、PZPは一般的には妊娠期にのみ増加するのに対し、α2Mは妊娠とは無関係に常に血漿中に1.5–2.0 mg/mLの濃度で存在し、両者の機能には大きな転換が生じていることが支持される[13][34]。

疾患や健康状態との関係

編集PZPはさまざまな疾患や健康状態と関係していることが観察されている。

PZPレベルの上昇と後のアルツハイマー病の発症との関連が観察されており、増加したPZPは脳に由来している可能性がある。さらに剖検では、アルツハイマー病患者の大脳皮質でのPZPの免疫反応性は老人斑と関係したミクログリアで特異的にみられ、一部の神経細胞でもみられた[35]。

HIV-1に感染した患者ではPZPレベルの上昇がみられる。PZPレベルは他の状況でも上昇するため、HIV-1の診断に利用できるだけの特異性はないが、治療や疾患の進行に対応したPZPレベルの経時変化が観察されれば、予後のマーカーとしての可能性がある[20]。

2018年の研究では、1型糖尿病の患者では血清中のPZPがダウンレギュレーションされていることが観察された[10]。

気管支拡張症の重症度と喀痰中のPZPレベルの間には有意な相関がみられる[36]。

マウスの血清を用いた、炎症性腸疾患の診断におけるPZPなどのタンパク質の有用性に関する研究では、PZPは複合バイオマーカーとして利用可能な6つのタンパク質の1つとして提案された[37]。

乳がん患者ではPZPの発現量には有意差がないことが判明したため、乳がんのバイオマーカーとしては不適格であると考えられる[38]。

体外受精とPZPの発現との関連も研究されており、PZPは体外受精の過程でアップレギュレーションされることが示された。 またPZPは、体外受精時の卵巣刺激反応不良群(POR)のバイオマーカーとなる可能性のあるタンパク質の一つであることが示された[8]。

出典

編集- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000126838 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000030359 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Entrez Gene: PZP pregnancy-zone protein”. 2021年4月17日閲覧。

- ^ Wong, Steve G.; Dessen, Andréa (2014-09-15). “Structure of a bacterial α2-macroglobulin reveals mimicry of eukaryotic innate immunity”. Nature Communications 5: 4917. doi:10.1038/ncomms5917. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 25221932.

- ^ a b Chiabrando, G. A.; Vides, M. A.; Sánchez, M. C. (2002-02-01). “Differential binding properties of human pregnancy zone protein- and alpha2-macroglobulin-proteinase complexes to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein”. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 398 (1): 73–78. doi:10.1006/abbi.2001.2659. ISSN 0003-9861. PMID 11811950.

- ^ a b Oh, Jae Won; Kim, Seul Ki; Cho, Kyung-Cho; Kim, Min-Sik; Suh, Chang Suk; Lee, Jung Ryeol; Kim, Kwang Pyo (2017-03). “Proteomic analysis of human follicular fluid in poor ovarian responders during in vitro fertilization”. Proteomics 17 (6). doi:10.1002/pmic.201600333. ISSN 1615-9861. PMID 28130869.

- ^ a b Charkoftaki, Georgia; Chen, Ying; Han, Ming; Sandoval, Monica; Yu, Xiaoqing; Zhao, Hongyu; Orlicky, David J.; Thompson, David C. et al. (2017-10-01). “Transcriptomic analysis and plasma metabolomics in Aldh16a1-null mice reveals a potential role of ALDH16A1 in renal function”. Chemico-Biological Interactions 276: 15–22. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2017.02.013. ISSN 1872-7786. PMC 5725231. PMID 28254523.

- ^ a b c do Nascimento de Oliveira, Valzimeire; Lima-Neto, Abelardo Barbosa Moreira; van Tilburg, Maurício Fraga; de Oliveira Monteiro-Moreira, Ana Cristina; Duarte Pinto Lobo, Marina; Rondina, Davide; Fernandes, Virgínia Oliveira; Montenegro, Ana Paula Dias Rangel et al. (2018). “Proteomic analysis to identify candidate biomarkers associated with type 1 diabetes”. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy 11: 289–301. doi:10.2147/DMSO.S162008. ISSN 1178-7007. PMC 6005324. PMID 29942143.

- ^ a b c Beckman, L.; Beckman, G.; Stigbrand, T. (1970). “Relation between the pregnancy zone protein and fetal sex”. Human Heredity 20 (5): 530–534. doi:10.1159/000152355. ISSN 0001-5652. PMID 5512126.

- ^ a b Smithies, O. (1959). “Zone electrophoresis in starch gels and its application to studies of serum proteins”. Advances in Protein Chemistry 14: 65–113. doi:10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60609-9. ISSN 0065-3233. PMID 13832188.

- ^ a b c d Sottrup-Jensen, L.; Folkersen, J.; Kristensen, T.; Tack, B. F. (1984-12-XX). “Partial primary structure of human pregnancy zone protein: extensive sequence homology with human alpha 2-macroglobulin”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 81 (23): 7353–7357. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.23.7353. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 392144. PMID 6209714.

- ^ Afonso, J. F.; De Alvarez, R. R. (1963-07-15). “Further starch gel fractionation of new protein zones in pregnancy”. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 86: 815–819. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(16)35199-7. ISSN 0002-9378. PMID 14011170.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Wyatt, Amy R.; Cater, Jordan H.; Ranson, Marie (2016-10). “PZP and PAI-2: Structurally-diverse, functionally similar pregnancy proteins?”. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 79: 113–117. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2016.08.018. ISSN 1878-5875. PMID 27554634.

- ^ a b Sand, O.; Folkersen, J.; Westergaard, J. G.; Sottrup-Jensen, L. (1985-12-15). “Characterization of human pregnancy zone protein. Comparison with human alpha 2-macroglobulin”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 260 (29): 15723–15735. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 2415522.

- ^ a b Poulsen, O. M.; Hau, J. (1988). “Interaction between pregnancy zone protein and plasmin”. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 243 (3): 157–164. doi:10.1007/BF00932082. ISSN 0932-0067. PMID 2971340.

- ^ “PZP - Pregnancy zone protein precursor - Homo sapiens (Human) - PZP gene & protein” (英語). www.uniprot.org. 2021年4月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b Tayade, Chandrakant; Esadeg, Souad; Fang, Yuan; Croy, B. A. (2005-12-21). “Functions of alpha 2 macroglobulins in pregnancy”. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 245 (1-2): 60–66. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2005.10.004. ISSN 0303-7207. PMID 16297527.

- ^ a b Sarcione, E. J.; Biddle, W. C. (2001-12-07). “Elevated serum pregnancy zone protein levels in HIV-1-infected men”. AIDS (London, England) 15 (18): 2467–2469. doi:10.1097/00002030-200112070-00023. ISSN 0269-9370. PMID 11774838.

- ^ Ekelund, L.; Laurell, C. B. (1994-12-XX). “The pregnancy zone protein response during gestation: a metabolic challenge”. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 54 (8): 623–629. doi:10.3109/00365519409087542. ISSN 0036-5513. PMID 7709165.

- ^ Damber, M. G.; von Schoultz, B.; Solheim, F.; Stigbrand, T. (1976-02-01). “A quantitative study of the pregnancy zone protein in sera of woman taking oral contraceptives”. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 124 (3): 289–292. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(76)90159-9. ISSN 0002-9378. PMID 55075.

- ^ Beckman, L.; Stigbrand, T.; von Schoultz, B. (1971). “Induction of the "pregnancy zone" protein by oral contraceptives”. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica 50 (4): 369–371. doi:10.3109/00016347109157341. ISSN 0001-6349. PMID 5157502.

- ^ a b c d e f Devriendt, K.; Van den Berghe, H.; Cassiman, J. J.; Marynen, P. (1991-01-17). “Primary structure of pregnancy zone protein. Molecular cloning of a full-length PZP cDNA clone by the polymerase chain reaction”. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta 1088 (1): 95–103. doi:10.1016/0167-4781(91)90157-h. ISSN 0006-3002. PMID 1989698.

- ^ Bohn, H.; Winckler, W. (1976-12-XX). “[Isolation and characterization of pregnancy associated alpha2 glycoprotein”]. Blut 33 (6): 377–388. doi:10.1007/BF00996570. ISSN 0006-5242. PMID 63301.

- ^ Sottrup-Jensen, L.; Folkersen, J.; Kristensen, T.; Tack, B. F. (1984-12-XX). “Partial primary structure of human pregnancy zone protein: extensive sequence homology with human alpha 2-macroglobulin”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 81 (23): 7353–7357. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.23.7353. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 392144. PMID 6209714.

- ^ a b c Marynen, P.; Devriendt, K.; Van den Berghe, H.; Cassiman, J. J. (1990-03-26). “A genetic polymorphism in a functional domain of human pregnancy zone protein: the bait region. Genomic structure of the bait domains of human pregnancy zone protein and alpha 2 macroglobulin”. FEBS letters 262 (2): 349–352. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(90)80226-9. ISSN 0014-5793. PMID 1692292.

- ^ Carlsson-Bosted, L.; Moestrup, S. K.; Gliemann, J.; Sottrup-Jensen, L.; Stigbrand, T. (1988-05-15). “Three different conformational states of pregnancy zone protein identified by monoclonal antibodies”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 263 (14): 6738–6741. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 3360802.

- ^ a b Jensen, P. E.; Hägglöf, E. M.; Arbelaez, L. F.; Stigbrand, T.; Shanbhag, V. P. (1993-07-10). “Comparison of conformational changes of pregnancy zone protein and human alpha 2-macroglobulin, a study using hydrophobic affinity partitioning”. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta 1164 (2): 152–158. doi:10.1016/0167-4838(93)90242-j. ISSN 0006-3002. PMID 7687148.

- ^ Skornicka, Erin L.; Kiyatkina, Nadya; Weber, Matthew C.; Tykocinski, Mark L.; Koo, Peter H. (2004-11-XX). “Pregnancy zone protein is a carrier and modulator of placental protein-14 in T-cell growth and cytokine production”. Cellular Immunology 232 (1-2): 144–156. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.03.007. ISSN 0008-8749. PMID 15882859.

- ^ Wu, S. M.; Patel, D. D.; Pizzo, S. V. (1998-10-15). “Oxidized alpha2-macroglobulin (alpha2M) differentially regulates receptor binding by cytokines/growth factors: implications for tissue injury and repair mechanisms in inflammation”. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 161 (8): 4356–4365. ISSN 0022-1767. PMID 9780213.

- ^ Wyatt, Amy R.; Kumita, Janet R.; Mifsud, Richard W.; Gooden, Cherrie A.; Wilson, Mark R.; Dobson, Christopher M. (2014-05-20). “Hypochlorite-induced structural modifications enhance the chaperone activity of human α2-macroglobulin”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (20): E2081–2090. doi:10.1073/pnas.1403379111. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 4034205. PMID 24799681.

- ^ Sánchez, M. C.; Chiabrando, G. A.; Guglielmone, H. A.; Bonacci, G. R.; Rabinovich, G. A.; Vides, M. A. (1998-08-XX). “Interaction of human tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) with pregnancy zone protein: a comparative study with t-PA-alpha2-macroglobulin interaction”. Journal of Biochemistry 124 (2): 274–279. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022107. ISSN 0021-924X. PMID 9685714.

- ^ Weström, B. R.; Karlsson, B. W.; Ohlsson, K. (1983-04-XX). “Immuno-cross-reactivity between alpha-macroglobulins from pig, dog, rat and man including human pregnancy-associated alpha 2-glycoprotein”. Hoppe-Seyler's Zeitschrift Fur Physiologische Chemie 364 (4): 375–381. doi:10.1515/bchm2.1983.364.1.375. ISSN 0018-4888. PMID 6190728.

- ^ Nijholt, Diana A. T.; Ijsselstijn, Linda; van der Weiden, Marcel M.; Zheng, Ping-Pin; Sillevis Smitt, Peter A. E.; Koudstaal, Peter J.; Luider, Theo M.; Kros, Johan M. (2015). “Pregnancy Zone Protein is Increased in the Alzheimer's Disease Brain and Associates with Senile Plaques”. Journal of Alzheimer's disease: JAD 46 (1): 227–238. doi:10.3233/JAD-131628. ISSN 1875-8908. PMID 25737043.

- ^ Smith, Alexandria; Choi, Jean-Yu; Finch, Simon; Ong, Samantha; Keir, Holly; Dicker, Alison; Chalmers, James (2017-09-XX). “Sputum Pregnancy Zone Protein (PZP) - a potential biomarker of bronchiectasis severity”. Respiratory Infections (European Respiratory Society): OA1969. doi:10.1183/1393003.congress-2017.OA1969.

- ^ Viennois, Emilie; Baker, Mark T.; Xiao, Bo; Wang, Lixin; Laroui, Hamed; Merlin, Didier (2015-01-01). “Longitudinal study of circulating protein biomarkers in inflammatory bowel disease”. Journal of Proteomics 112: 166–179. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2014.09.002. ISSN 1876-7737. PMC 4312267. PMID 25230104.

- ^ Petersen, C. M.; Jensen, P. H.; Bukh, A.; Sunde, L.; Lamm, L. U.; Ingerslev, J. (1990-09-XX). “Pregnancy zone protein: a re-evaluation of serum levels in healthy women and in women suffering from breast cancer or trophoblastic disease”. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 50 (5): 479–485. doi:10.1080/00365519009089162. ISSN 0036-5513. PMID 1700464.

関連文献

編集- “Enzymatic activity of prostate-specific antigen and its reactions with extracellular serine proteinase inhibitors.”. Eur. J. Biochem. 194 (3): 755–63. (1991). doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19466.x. PMID 1702714.

- “Human fibroblast collagenase-alpha-macroglobulin interactions. Localization of cleavage sites in the bait regions of five mammalian alpha-macroglobulins.”. J. Biol. Chem. 264 (1): 393–401. (1989). PMID 2462561.

- “The alpha-macroglobulin bait region. Sequence diversity and localization of cleavage sites for proteinases in five mammalian alpha-macroglobulins.”. J. Biol. Chem. 264 (27): 15781–9. (1989). PMID 2476433.

- “Pregnancy zone protein, a proteinase-binding macroglobulin. Interactions with proteinases and methylamine.”. Biochemistry 28 (24): 9324–31. (1990). doi:10.1021/bi00450a012. PMID 2692707.

- “Binding of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) to pregnancy zone protein (PZP). Comparison to the TGF-beta-alpha 2-macroglobulin interaction.”. Eur. J. Biochem. 221 (2): 687–93. (1994). doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18781.x. PMID 7513640.

- “Preparation and characterization of a C-terminal fragment of pregnancy zone protein corresponding to the receptor-binding peptide from human alpha 2-macroglobulin.”. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1293 (2): 254–8. (1996). doi:10.1016/0167-4838(95)00257-x. PMID 8620037.

- “Activated human plasma carboxypeptidase B is retained in the blood by binding to alpha2-macroglobulin and pregnancy zone protein.”. J. Biol. Chem. 271 (22): 12937–43. (1996). doi:10.1074/jbc.271.22.12937. PMID 8662763.

- “Interaction of matrix metalloproteinases-2 and -9 with pregnancy zone protein and alpha2-macroglobulin.”. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 347 (1): 62–8. (1997). doi:10.1006/abbi.1997.0309. PMID 9344465.

- “Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences.”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. (2003). doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- “The human plasma proteome: a nonredundant list developed by combination of four separate sources.”. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3 (4): 311–26. (2004). doi:10.1074/mcp.M300127-MCP200. PMID 14718574.

- “Human plasma N-glycoproteome analysis by immunoaffinity subtraction, hydrazide chemistry, and mass spectrometry.”. J. Proteome Res. 4 (6): 2070–80. (2006). doi:10.1021/pr0502065. PMC 1850943. PMID 16335952.

- “Diversification of transcriptional modulation: large-scale identification and characterization of putative alternative promoters of human genes.”. Genome Res. 16 (1): 55–65. (2006). doi:10.1101/gr.4039406. PMC 1356129. PMID 16344560.

- “Proteolytic hydrolysis and purification of the LRP/alfa-2-macroglobulin receptor domain from alpha-macroglobulins.”. Protein Expr. Purif. 53 (1): 112–8. (2007). doi:10.1016/j.pep.2006.12.008. PMID 17257854.