プロテオパチー

医学では、プロテオパチー (proteopathy; プロテオパシーとも) ([proʊtiːˈɒpəθiː]; Proteo- [pref. protein]; -pathy [suff. disease]; proteopathies pl.; proteopathic adj) は、特定のタンパク質が構造的に異常になり、体の細胞、組織、臓器の機能を破壊する疾患のクラスを指す[1][2]。多くの場合、タンパク質は正常な構成にフォールディング (折り畳み) できない。このミスフォールディング (誤った折り畳み) 状態では、タンパク質は何らかの方法で毒性になるか (毒性機能獲得)、または通常の機能を失う可能性がある[3]。

| プロテオパチー | |

|---|---|

| |

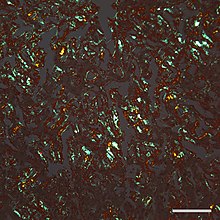

| 老人斑 (senile plaques) と脳アミロイドアンギオパチー (脳アミロイド血管症) に蓄積するタンパク質断片である「アミロイドβ」(Aβ)(茶色) に対する抗体で免疫染色した、アルツハイマー病患者からの大脳皮質の切片の顕微鏡写真。10倍顕微鏡対物レンズ。 | |

| 概要 | |

| 分類および外部参照情報 |

プロテオパチー (proteopathies) (別名: プロテイノパチー (proteinopathies)、タンパク質構造障害 (protein conformational disorders)、またはタンパク質のミスフォールディング疾患 (protein misfolding diseases) として知られている) は、クロイツフェルト・ヤコブ病や他のプリオン病、アルツハイマー病、パーキンソン病、アミロイドーシス、多系統萎縮症、および他の疾患の広い範囲が含まれている(プロテオパチーのリストを参照)[2][4][5][6][7][8]。プロテオパチー (proteopathy) という用語は、最初にラリー・ウォーカー (Lary Walker) とハリー・レヴィン (Harry LeVine) によって2000年に提案された[9]。

プロテオパチーの概念は、その起源を19世紀半ばまで遡ることができ、1854年、ルドルフ・ウィルヒョウ (Rudolf Virchow) は、アミロイド (amyloid; デンプンのような) という用語を作り、セルロースに似た化学反応を示す大脳アミロイド小体の物質を説明した。1859年、フリードライヒ (Friedreich) とケクレ (Kekulé) は、「アミロイド」がセルロースからなるのではなく、実際にはタンパク質を豊富に含んでいることを示した[10]。その後の研究では、多くの異なるタンパク質がアミロイドを形成し、それらは、コンゴーレッド染色後の偏光顕微鏡観察時の交差偏光下での複屈折性や、電子顕微鏡で観察されるフィブリル状 (繊維状) の超微細構造、という共通点を持っていることが示されている[10]。しかし、いくつかの蛋白質性病変は複屈折を欠き、アルツハイマー病患者の脳内にアミロイドβ (Aβ) タンパク質がびまん性に沈着しているような古典的なアミロイド線維をほとんど含まないか、または全く含まない[11]。さらに、罹患臓器の細胞に毒性があるのはオリゴマーとして知られている小さな非フィブリル性タンパク質の凝集体であり、フィブリル性形態のアミロイド原性タンパク質は比較的良性である可能性があるという証拠が明らかになった[12][13]。

病態生理

編集ほとんどの場合、すべてのプロテオパチーではないにしても、3次元フォールディング (コンフォメーション)の変化により、特定のタンパク質がそれ自体に結合する傾向が高まる[14]。この凝集形態では、タンパク質は除去 (clearance; クリアランス) に対する抵抗性があり、影響を受ける臓器の正常な能力を妨害する可能性がある。場合によっては、タンパク質のミスフォールディングにより、通常の機能が失われる。例えば、嚢胞性線維症は、嚢胞性線維症膜貫通調節因子 (CFTR) タンパク質の欠陥によって引き起こされ[15]、筋萎縮性側索硬化症/前頭側頭葉変性症 (FTLD) では、特定の遺伝子調節タンパク質が細胞質内で不適切に凝集し、核内での通常の役割を実行できない[16][17]。タンパク質は、ポリペプチド骨格として知られる共通の構造的特徴を共有しているため、すべてのタンパク質は、ある状況下でミスフォールドされる可能性がある[18]。しかし、おそらく脆弱なタンパク質の構造的特異性のために、比較的少数のタンパク質のみがタンパク質変性疾患に関連している。例えば、通常はアンフォールド (折り畳まれていない) されているか、またはモノマーとして比較的不安定なタンパク質 (つまり、単一の非結合タンパク質分子) は、異常なコンフォメーションにミスフォールドする可能性が高くなる[14][18][19]。ほぼ全ての場合において、疾患を引き起こす分子構成には、タンパク質のβシート二次構造の増加を伴う[14][18][20][21]。いくつかのプロテオパチーにおける異常なタンパク質は、複数の3次元形状に折りたたまれることが示されている。これらの変性タンパク質構造は、それらの異なる病原性、生化学的、およびコンフォメーション特性によって定義される[22]。これらはプリオン病に関して最も徹底的に研究されており、タンパク質株と呼ばれている[23][24]。

プロテオパチーが発症する可能性は、タンパク質の自己組織化を促進する特定の危険因子によって増加する。これらは、タンパク質の一次アミノ酸配列の不安定化変化、翻訳後修飾 (過剰リン酸化など)、温度やpHの変化、タンパク質の生産量の増加、またはその除去 (クリアランス) の減少が含まれている[25][26][27]。加齢は、外傷性脳損傷と同様に[28][29]、強い危険因子である[25]。老化した脳では、複数のプロテオパチーが重畳する可能性がある[30]。例えば、タウオパチーとAβアミロイドーシス (アルツハイマー病の重要な病理学的特徴として共存する) に加えて、多くのアルツハイマー病患者は脳内にシヌクレイノパチー (レビー小体) を併発している[31]。

シャペロンやコ・シャペロン (タンパク質のフォールディングを助けるタンパク質) が、加齢や蛋白質ミスフォールディング病において、タンパク質の毒性に拮抗し、タンパク質恒常性を維持しているのではないかという仮説が立てられている[32][33][34]。

播種誘発(seeded induction)

編集いくつかのタンパク質は、疾患を引き起こすコンフォメーションに折り畳まれた同じ (または類似の) タンパク質への曝露によって、異常な集合体を形成するように誘導でき、これは「播種 (seeding)」または「許容テンプレート化 (permissive templating)」と呼ばれるプロセスである[35][36]。このようにして、罹患したドナーから罹患組織抽出物を導入することにより、易罹患性宿主に疾患状態を引き起こすことができる。そのような誘導性プロテオパチーの最もよく知られている形態はプリオン病であり[37]、これは、疾患を引き起こすコンフォメーションの精製プリオンタンパク質に、宿主生物を曝露することによって感染する可能性がある[38][39]。現在、Aβアミロイドーシス、アミロイドA (AA) アミロイドーシス、およびアポリポプロテインA-IIアミロイドーシス[36][40]、タウオパチー[41]、シヌクレイノパチー[42][43][44][45]、およびスーパーオキシドジスムターゼ-1 (SOD1)[46][47]、ポリグルタミン[48][49]、およびTAR DNA結合タンパク-43 (TDP-43) の凝集を含む[50]、他のプロテオパチーが同様のメカニズムによって誘発されるという証拠がある。

これらの例のすべてにおいて、タンパク質の異常な形態自体が病原体であるように見える。場合によっては、あるタイプのタンパク質の沈着は、おそらくタンパク質分子の構造的相補性のために、βシート構造に富む他のタンパク質の集合体によって実験的に誘発されることがある。例えば、AAアミロイドーシスは、絹、酵母アミロイドSup35、大腸菌 (Escherichia coli) 由来のカーリー線維 (curli fibrils) などの多様な高分子によってマウスで刺激される[51]。さらに、アポリポプロテインA-IIアミロイドは、βシートを豊富に含む様々なアミロイド原線維によってマウスで誘発され[52]、脳タウオパチーは、凝集したAβを豊富に含む脳抽出物によって誘導される[53]。また、プリオンタンパク質とAβとの交雑播種 (cross-seeding) の実験的証拠もある[54]。一般に、このような異種播種は、同じタンパク質の破損した形態による播種よりも効率が悪い。

プロテオパチーのリスト

編集リンク先は英語版サイト。

治療

編集多くのプロテオパチーのための効果的な治療法の開発は、挑戦的である[80][81]。プロテオパチーは、多くの場合、異なる原因から生じる異なるタンパク質が関与しているため、治療戦略はそれぞれの疾患に合わせてカスタマイズする必要がある。しかし、一般的な治療法としては、罹患した臓器の機能を維持し、疾患の原因となるタンパク質の形成を減少させ、タンパク質のミスフォールディングおよび/または凝集を防止し、またはそれらの除去の促進が含まれる[82][80][83]。例えば、アルツハイマー病では、疾患関連タンパク質Aβを親タンパク質から遊離させる酵素を阻害することにより、疾患関連タンパク質Aβの産生を減らす方法が研究されている[81]。別の戦略は、抗体を用いて能動的または受動的な免疫化によって特定のタンパク質を中和することである[84]。いくつかのプロテオパチーでは、タンパク質オリゴマーの毒性作用を阻害することが有益な場合がある[85]。アミロイドA (AA) アミロイドーシスは、血中のタンパク質 (血清アミロイドA、またはSAA呼ばれる) の量を増加させる炎症状態を治療することによって減少できる[80]。免疫グロブリン軽鎖アミロイドーシス(ALアミロイドーシス)では、化学療法により、様々な体の臓器でアミロイドを形成する軽鎖タンパク質を作る血球の数を減らすことができる[86]。トランスサイレチン (TTR) アミロイドーシス (ATTR) は、ミスフォールドされたTTRが複数の臓器に沈着することに起因する[87]。TTRは主に肝臓で産生されるため、TTRアミロイドーシスは、一部の遺伝性症例では、肝移植により進行を遅らせられる可能性がある[88]。TTRアミロイドーシスはまた、タンパク質の正常な集合体 (4つのTTR分子が結合して構成されているため、テトラマーと呼ばれる) を安定化させることによって治療できる。安定化により、個々のTTR分子が逃げたり、ミスフォールディングしたり、アミロイドに凝集するのを防ぐことができる[89][90]。プロテオパチーのための他のいくつかの治療戦略が研究されているが、これには、低分子 (small molecule) および低分子干渉RNA (siRNA)、アンチセンスオリゴヌクレオチド、ペプチド、および人工免疫細胞などの生物学的医薬品が含まれる[91][92][93][94]。場合によっては、複数の治療薬を組み合わせて効果を高めることもある[92][95]。

追加画像

編集-

アルツハイマー病患者の大脳皮質の神経細胞体 (矢印) と突起 (process)(矢尻) のタウオパチー (茶色) の顕微鏡写真。バー=25ミクロン (0.025 mm)。

参考文献

編集- ^ Walker LC, LeVine H (2000). “The cerebral proteopathies”. Neurobiology of Aging 21 (4): 559–61. doi:10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00160-3. PMID 10924770.

- ^ a b Walker LC, LeVine H (2000). “The cerebral proteopathies: neurodegenerative disorders of protein conformation and assembly”. Molecular Neurobiology 21 (1–2): 83–95. doi:10.1385/MN:21:1-2:083. PMID 11327151.

- ^ Luheshi LM, Crowther DC, Dobson CM (February 2008). “Protein misfolding and disease: from the test tube to the organism”. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 12 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.02.011. PMID 18295611.

- ^ Chiti F, Dobson CM (2006). “Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease”. Annual Review of Biochemistry 75 (1): 333–66. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. PMID 16756495.

- ^ Carrell RW, Lomas DA (July 1997). “Conformational disease”. Lancet 350 (9071): 134–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02073-4. PMID 9228977.

- ^ Westermark P, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, Cohen AS, Frangione B, Ikeda S, Masters CL, Merlini G, Saraiva MJ, Sipe JD (September 2007). “A primer of amyloid nomenclature”. Amyloid 14 (3): 179–83. doi:10.1080/13506120701460923. PMID 17701465.

- ^ Westermark GT, Fändrich M, Lundmark K, Westermark P (January 2018). “Noncerebral Amyloidoses: Aspects on Seeding, Cross-Seeding, and Transmission”. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 8 (1): a024323. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a024323. PMID 28108533.

- ^ Prusiner SB (2013). “Biology and genetics of prions causing neurodegeneration”. Annual Review of Genetics 47: 601–23. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155524. PMC 4010318. PMID 24274755.

- ^ Walker LC, LeVine H (2000). “The cerebral proteopathies”. Neurobiology of Aging 21 (4): 559–61. doi:10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00160-3. PMID 10924770.

- ^ a b Sipe JD, Cohen AS (June 2000). “Review: history of the amyloid fibril”. Journal of Structural Biology 130 (2–3): 88–98. doi:10.1006/jsbi.2000.4221. PMID 10940217.

- ^ Wisniewski HM, Sadowski M, Jakubowska-Sadowska K, Tarnawski M, Wegiel J (July 1998). “Diffuse, lake-like amyloid-beta deposits in the parvopyramidal layer of the presubiculum in Alzheimer disease”. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology 57 (7): 674–83. doi:10.1097/00005072-199807000-00004. PMID 9690671.

- ^ Glabe CG (April 2006). “Common mechanisms of amyloid oligomer pathogenesis in degenerative disease”. Neurobiology of Aging 27 (4): 570–5. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.04.017. PMID 16481071.

- ^ Gadad BS, Britton GB, Rao KS (2011). “Targeting oligomers in neurodegenerative disorders: lessons from α-synuclein, tau, and amyloid-β peptide”. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 24 Suppl 2: 223–32. doi:10.3233/JAD-2011-110182. PMID 21460436.

- ^ a b c Carrell RW, Lomas DA (July 1997). “Conformational disease”. Lancet 350 (9071): 134–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02073-4. PMID 9228977.

- ^ Luheshi LM, Crowther DC, Dobson CM (February 2008). “Protein misfolding and disease: from the test tube to the organism”. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 12 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.02.011. PMID 18295611.

- ^ Ito D, Suzuki N (October 2011). “Conjoint pathologic cascades mediated by ALS/FTLD-U linked RNA-binding proteins TDP-43 and FUS”. Neurology 77 (17): 1636–43. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182343365. PMC 3198978. PMID 21956718.

- ^ Wolozin B, Apicco D (2015). “RNA binding proteins and the genesis of neurodegenerative diseases”. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 822: 11–5. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08927-0_3. ISBN 978-3-319-08926-3. PMC 4694570. PMID 25416971.

- ^ a b c Dobson CM (September 1999). “Protein misfolding, evolution and disease”. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 24 (9): 329–32. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01445-0. PMID 10470028.

- ^ Jucker M, Walker LC (September 2013). “Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases”. Nature 501 (7465): 45–51. doi:10.1038/nature12481. PMC 3963807. PMID 24005412.

- ^ Selkoe DJ (December 2003). “Folding proteins in fatal ways”. Nature 426 (6968): 900–4. doi:10.1038/nature02264. PMID 14685251.

- ^ Eisenberg D, Jucker M (March 2012). “The amyloid state of proteins in human diseases”. Cell 148 (6): 1188–203. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.022. PMC 3353745. PMID 22424229.

- ^ Walker LC (November 2016). “Proteopathic Strains and the Heterogeneity of Neurodegenerative Diseases”. Annual Review of Genetics 50: 329–346. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-034943. PMC 6690197. PMID 27893962.

- ^ Collinge J, Clarke AR (November 2007). “A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity”. Science 318 (5852): 930–6. doi:10.1126/science.1138718. PMID 17991853.

- ^ Colby DW, Prusiner SB (September 2011). “De novo generation of prion strains”. Nature Reviews. Microbiology 9 (11): 771–7. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2650. PMC 3924856. PMID 21947062.

- ^ a b Walker LC, LeVine H (2000). “The cerebral proteopathies”. Neurobiology of Aging 21 (4): 559–61. doi:10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00160-3. PMID 10924770.

- ^ Carrell RW, Lomas DA (July 1997). “Conformational disease”. Lancet 350 (9071): 134–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02073-4. PMID 9228977.

- ^ Dobson CM (September 1999). “Protein misfolding, evolution and disease”. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 24 (9): 329–32. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01445-0. PMID 10470028.

- ^ DeKosky ST, Ikonomovic MD, Gandy S (September 2010). “Traumatic brain injury--football, warfare, and long-term effects”. The New England Journal of Medicine 363 (14): 1293–6. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1007051. PMID 20879875.

- ^ McKee AC, Stein TD, Kiernan PT, Alvarez VE (May 2015). “The neuropathology of chronic traumatic encephalopathy”. Brain Pathology 25 (3): 350–64. doi:10.1111/bpa.12248. PMC 4526170. PMID 25904048.

- ^ Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, Bouras C, Braak H, Cairns NJ, Castellani RJ, Crain BJ, Davies P, Del Tredici K, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Haroutunian V, Hof PR, Hulette CM, Hyman BT, Iwatsubo T, Jellinger KA, Jicha GA, Kövari E, Kukull WA, Leverenz JB, Love S, Mackenzie IR, Mann DM, Masliah E, McKee AC, Montine TJ, Morris JC, Schneider JA, Sonnen JA, Thal DR, Trojanowski JQ, Troncoso JC, Wisniewski T, Woltjer RL, Beach TG (May 2012). “Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature”. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology 71 (5): 362–81. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e31825018f7. PMC 3560290. PMID 22487856.

- ^ Mrak RE, Griffin WS (2007). “Dementia with Lewy bodies: Definition, diagnosis, and pathogenic relationship to Alzheimer's disease”. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 3 (5): 619–25. PMC 2656298. PMID 19300591.

- ^ Douglas PM, Summers DW, Cyr DM (2009). “Molecular chaperones antagonize proteotoxicity by differentially modulating protein aggregation pathways”. Prion 3 (2): 51–8. doi:10.4161/pri.3.2.8587. PMC 2712599. PMID 19421006.

- ^ Brehme M, Voisine C, Rolland T, Wachi S, Soper JH, Zhu Y, Orton K, Villella A, Garza D, Vidal M, Ge H, Morimoto RI (November 2014). “A chaperome subnetwork safeguards proteostasis in aging and neurodegenerative disease”. Cell Reports 9 (3): 1135–50. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.042. PMC 4255334. PMID 25437566.

- ^ Brehme M, Voisine C (August 2016). “Model systems of protein-misfolding diseases reveal chaperone modifiers of proteotoxicity”. Disease Models & Mechanisms 9 (8): 823–38. doi:10.1242/dmm.024703. PMC 5007983. PMID 27491084.

- ^ Hardy J (August 2005). “Expression of normal sequence pathogenic proteins for neurodegenerative disease contributes to disease risk: 'permissive templating' as a general mechanism underlying neurodegeneration”. Biochemical Society Transactions 33 (Pt 4): 578–81. doi:10.1042/BST0330578. PMID 16042548.

- ^ a b Walker LC, Levine H, Mattson MP, Jucker M (August 2006). “Inducible proteopathies”. Trends in Neurosciences 29 (8): 438–43. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2006.06.010. PMID 16806508.

- ^ Prusiner SB (May 2001). “Shattuck lecture--neurodegenerative diseases and prions”. The New England Journal of Medicine 344 (20): 1516–26. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105173442006. PMID 11357156.

- ^ Zou WQ, Gambetti P (April 2005). “From microbes to prions the final proof of the prion hypothesis”. Cell 121 (2): 155–7. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.002. PMID 15851020.

- ^ Ma J (2012). “The role of cofactors in prion propagation and infectivity”. PLoS Pathogens 8 (4): e1002589. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002589. PMC 3325206. PMID 22511864.

- ^ Meyer-Luehmann M, Coomaraswamy J, Bolmont T, Kaeser S, Schaefer C, Kilger E, Neuenschwander A, Abramowski D, Frey P, Jaton AL, Vigouret JM, Paganetti P, Walsh DM, Mathews PM, Ghiso J, Staufenbiel M, Walker LC, Jucker M (September 2006). “Exogenous induction of cerebral beta-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host”. Science 313 (5794): 1781–4. doi:10.1126/science.1131864. PMID 16990547.

- ^ Clavaguera F, Bolmont T, Crowther RA, Abramowski D, Frank S, Probst A, Fraser G, Stalder AK, Beibel M, Staufenbiel M, Jucker M, Goedert M, Tolnay M (July 2009). “Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain”. Nature Cell Biology 11 (7): 909–13. doi:10.1038/ncb1901. PMC 2726961. PMID 19503072.

- ^ Desplats P, Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Patrick C, Rockenstein E, Crews L, Spencer B, Masliah E, Lee SJ (August 2009). “Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha-synuclein”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (31): 13010–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903691106. PMC 2722313. PMID 19651612.

- ^ Hansen C, Angot E, Bergström AL, Steiner JA, Pieri L, Paul G, Outeiro TF, Melki R, Kallunki P, Fog K, Li JY, Brundin P (February 2011). “α-Synuclein propagates from mouse brain to grafted dopaminergic neurons and seeds aggregation in cultured human cells”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 121 (2): 715–25. doi:10.1172/JCI43366. PMC 3026723. PMID 21245577.

- ^ Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Freeman TB, Olanow CW (May 2008). “Lewy body-like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson's disease”. Nature Medicine 14 (5): 504–6. doi:10.1038/nm1747. PMID 18391962.

- ^ Kordower JH, Dodiya HB, Kordower AM, Terpstra B, Paumier K, Madhavan L, Sortwell C, Steece-Collier K, Collier TJ (September 2011). “Transfer of host-derived α synuclein to grafted dopaminergic neurons in rat”. Neurobiology of Disease 43 (3): 552–7. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2011.05.001. PMC 3430516. PMID 21600984.

- ^ Münch C, O'Brien J, Bertolotti A (March 2011). “Prion-like propagation of mutant superoxide dismutase-1 misfolding in neuronal cells”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (9): 3548–53. doi:10.1073/pnas.1017275108. PMC 3048161. PMID 21321227.

- ^ Chia R, Tattum MH, Jones S, Collinge J, Fisher EM, Jackson GS (May 2010). Feany, Mel B.. ed. “Superoxide dismutase 1 and tgSOD1 mouse spinal cord seed fibrils, suggesting a propagative cell death mechanism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis”. PLOS One 5 (5): e10627. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010627. PMC 2869360. PMID 20498711.

- ^ Ren PH, Lauckner JE, Kachirskaia I, Heuser JE, Melki R, Kopito RR (February 2009). “Cytoplasmic penetration and persistent infection of mammalian cells by polyglutamine aggregates”. Nature Cell Biology 11 (2): 219–25. doi:10.1038/ncb1830. PMC 2757079. PMID 19151706.

- ^ Pearce MM, Kopito RR (February 2018). “Prion-Like Characteristics of Polyglutamine-Containing Proteins”. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 8 (2): a024257. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a024257. PMC 5793740. PMID 28096245.

- ^ Furukawa Y, Kaneko K, Watanabe S, Yamanaka K, Nukina N (May 2011). “A seeding reaction recapitulates intracellular formation of Sarkosyl-insoluble transactivation response element (TAR) DNA-binding protein-43 inclusions”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 286 (21): 18664–72. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.231209. PMC 3099683. PMID 21454603.

- ^ Lundmark K, Westermark GT, Olsén A, Westermark P (April 2005). “Protein fibrils in nature can enhance amyloid protein A amyloidosis in mice: Cross-seeding as a disease mechanism”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (17): 6098–102. doi:10.1073/pnas.0501814102. PMC 1087940. PMID 15829582.

- ^ Fu X, Korenaga T, Fu L, Xing Y, Guo Z, Matsushita T, Hosokawa M, Naiki H, Baba S, Kawata Y, Ikeda S, Ishihara T, Mori M, Higuchi K (April 2004). “Induction of AApoAII amyloidosis by various heterogeneous amyloid fibrils”. FEBS Letters 563 (1–3): 179–84. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00295-9. PMID 15063745.

- ^ Bolmont T, Clavaguera F, Meyer-Luehmann M, Herzig MC, Radde R, Staufenbiel M, Lewis J, Hutton M, Tolnay M, Jucker M (December 2007). “Induction of tau pathology by intracerebral infusion of amyloid-beta -containing brain extract and by amyloid-beta deposition in APP x Tau transgenic mice”. The American Journal of Pathology 171 (6): 2012–20. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2007.070403. PMC 2111123. PMID 18055549.

- ^ Morales R, Estrada LD, Diaz-Espinoza R, Morales-Scheihing D, Jara MC, Castilla J, Soto C (March 2010). “Molecular cross talk between misfolded proteins in animal models of Alzheimer's and prion diseases”. The Journal of Neuroscience 30 (13): 4528–35. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5924-09.2010. PMC 2859074. PMID 20357103.

- ^ Jucker M, Walker LC (September 2013). “Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases”. Nature 501 (7465): 45–51. doi:10.1038/nature12481. PMC 3963807. PMID 24005412.

- ^ a b c d Revesz T, Ghiso J, Lashley T, Plant G, Rostagno A, Frangione B, Holton JL (September 2003). “Cerebral amyloid angiopathies: a pathologic, biochemical, and genetic view”. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology 62 (9): 885–98. doi:10.1093/jnen/62.9.885. PMID 14533778.

- ^ Guo L, Salt TE, Luong V, Wood N, Cheung W, Maass A, Ferrari G, Russo-Marie F, Sillito AM, Cheetham ME, Moss SE, Fitzke FW, Cordeiro MF (August 2007). “Targeting amyloid-beta in glaucoma treatment”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (33): 13444–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703707104. PMC 1940230. PMID 17684098.

- ^ Prusiner, SB (2004). Prion Biology and Diseases (2 ed.). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 0-87969-693-1

- ^ Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Del Tredici K, Braak H (January 2013). “100 years of Lewy pathology”. Nature Reviews. Neurology 9 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2012.242. PMID 23183883.

- ^ Clavaguera F, Hench J, Goedert M, Tolnay M (February 2015). “Invited review: Prion-like transmission and spreading of tau pathology”. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology 41 (1): 47–58. doi:10.1111/nan.12197. PMID 25399729.

- ^ a b Mann DM, Snowden JS (November 2017). “Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: Pathogenesis, pathology and pathways to phenotype”. Brain Pathology 27 (6): 723–736. doi:10.1111/bpa.12486. PMID 28100023.

- ^ Grad LI, Fernando SM, Cashman NR (May 2015). “From molecule to molecule and cell to cell: prion-like mechanisms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis”. Neurobiology of Disease 77: 257–65. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2015.02.009. PMID 25701498.

- ^ Ludolph AC, Brettschneider J, Weishaupt JH (October 2012). “Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis”. Current Opinion in Neurology 25 (5): 530–5. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e328356d328. PMID 22918486.

- ^ Orr HT, Zoghbi HY (July 2007). “Trinucleotide repeat disorders”. Annual Review of Neuroscience 30 (1): 575–621. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113042. PMID 17417937.

- ^ Almeida B, Fernandes S, Abreu IA, Macedo-Ribeiro S (2013). “Trinucleotide repeats: a structural perspective”. Frontiers in Neurology 4: 76. doi:10.3389/fneur.2013.00076. PMC 3687200. PMID 23801983.

- ^ Spinner NB (March 2000). “CADASIL: Notch signaling defect or protein accumulation problem?”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 105 (5): 561–2. doi:10.1172/JCI9511. PMC 292459. PMID 10712425.

- ^ Quinlan RA, Brenner M, Goldman JE, Messing A (June 2007). “GFAP and its role in Alexander disease”. Experimental Cell Research 313 (10): 2077–87. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.004. PMC 2702672. PMID 17498694.

- ^ Ito D, Suzuki N (January 2009). “Seipinopathy: a novel endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated disease”. Brain 132 (Pt 1): 8–15. doi:10.1093/brain/awn216. PMID 18790819.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Sipe JD, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, Ikeda SI, Merlini G, Saraiva MJ, Westermark P (December 2016). “Amyloid fibril proteins and amyloidosis: chemical identification and clinical classification International Society of Amyloidosis 2016 Nomenclature Guidelines”. Amyloid 23 (4): 209–213. doi:10.1080/13506129.2016.1257986. PMID 27884064.

- ^ Lomas DA, Carrell RW (October 2002). “Serpinopathies and the conformational dementias”. Nature Reviews Genetics 3 (10): 759–68. doi:10.1038/nrg907. PMID 12360234.

- ^ Mukherjee A, Soto C (May 2017). “Prion-Like Protein Aggregates and Type 2 Diabetes”. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 7 (5): a024315. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a024315. PMC 5411686. PMID 28159831.

- ^ Askanas V, Engel WK (January 2006). “Inclusion-body myositis: a myodegenerative conformational disorder associated with Abeta, protein misfolding, and proteasome inhibition”. Neurology 66 (2 Suppl 1): S39-48. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000192128.13875.1e. PMID 16432144.

- ^ Ecroyd H, Carver JA (January 2009). “Crystallin proteins and amyloid fibrils”. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 66 (1): 62–81. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8327-4. PMID 18810322.

- ^ Surguchev A, Surguchov A (January 2010). “Conformational diseases: looking into the eyes”. Brain Research Bulletin 81 (1): 12–24. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.09.015. PMID 19808079.

- ^ Huilgol SC, Ramnarain N, Carrington P, Leigh IM, Black MM (May 1998). “Cytokeratins in primary cutaneous amyloidosis”. The Australasian Journal of Dermatology 39 (2): 81–5. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.1998.tb01253.x. PMID 9611375.

- ^ Janig E, Stumptner C, Fuchsbichler A, Denk H, Zatloukal K (March 2005). “Interaction of stress proteins with misfolded keratins”. European Journal of Cell Biology 84 (2–3): 329–39. doi:10.1016/j.ejcb.2004.12.018. PMID 15819411.

- ^ D'Souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, Dogan A (June 2014). “Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration”. Amyloid 21 (2): 71–5. doi:10.3109/13506129.2013.876984. PMC 4021035. PMID 24446896.

- ^ Meng X, Clews J, Kargas V, Wang X, Ford RC (January 2017). “The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and its stability”. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 74 (1): 23–38. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2386-8. PMC 5209436. PMID 27734094.

- ^ Stuart MJ, Nagel RL (2004). “Sickle-cell disease”. Lancet 364 (9442): 1343–60. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17192-4. PMID 15474138.

- ^ a b c Pepys MB (2006). “Amyloidosis”. Annu Rev Med 57: 223-241. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131243. PMID 16409147.

- ^ a b Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM (2011). “Alzheimer's disease: the challenge of the second century”. Sci Transl Med 3 (77): 77sr1. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. PMC 3130546. PMID 21471435.

- ^ Pepys MB (2001). “Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of systemic amyloidosis”. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B 356: 203-211. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0766. PMC 1088426. PMID 11260801.

- ^ Walker LC, LeVine H 3rd (2002). “Proteopathy: the next therapeutic frontier?”. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 3 (5): 782–7. PMID 12090553.

- ^ Braczynski AK, Schulz JB, Bach JP (2017). “Vaccination strategies in tauopathies and synucleinopathies”. J Neurochem 143 (5): 467-488. doi:10.1111/jnc.14207. PMID 28869766.

- ^ Klein WL (2013). “Synaptotoxic amyloid-β oligomers: a molecular basis for the cause, diagnosis, and treatment of Alzheimer's disease?”. J Alzheimers Dis 33 (Suppl 1): S49-65. doi:10.3233/JAD-2012-129039. PMID 22785404.

- ^ Badar T, D'Souza A, Hari P (2018). “Recent advances in understanding and treating immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis”. F1000Res 7: 1348. doi:10.12688/f1000research.15353.1. PMC 6117860. PMID 30228867.

- ^ Carvalho A, Rocha A, Lobato L (2015). “Liver transplantation in transthyretin amyloidosis: issues and challenges”. Liver Transpl 21 (3): 282-292. doi:10.1002/lt.24058. PMID 25482846.

- ^ Suhr OB, Herlenius G, Friman S, Ericzon BG (2000). “Liver transplantation for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis”. Liver Transpl 6 (3): 263-276. doi:10.1053/lv.2000.6145. PMID 10827225.

- ^ Suhr OB, Larsson M, Ericzon BG, Wilczek HE et al (2016). “Survival After Transplantation in Patients With Mutations Other Than Val30Met: Extracts From the FAP World Transplant Registry”. Transplantation 100 (2): 373-381. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000001021. PMC 4732012. PMID 26656838.

- ^ Coelho T et al (2016). “Mechanism of Action and Clinical Application of Tafamidis in Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis”. Neurol Ther 5 (1): 1-25. doi:10.1007/s40120-016-0040-x. PMC 4919130. PMID 26894299.

- ^ Suhr OB, Larsson M, Ericzon BG, Wilczek HE et al (2016). “Survival After Transplantation in Patients With Mutations Other Than Val30Met: Extracts From the FAP World Transplant Registry”. Transplantation 100 (2): 373-381. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000001021. PMC 4732012. PMID 26656838.

- ^ a b Badar T, D'Souza A, Hari P (2018). “Recent advances in understanding and treating immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis”. F1000Res 7: 1348. doi:10.12688/f1000research.15353.1. PMC 6117860. PMID 30228867.

- ^ Yu D et al (2012). “Single-stranded RNAs use RNAi to potently and allele-selectively inhibit mutant huntingtin expression”. Cell 150 (5): 895-908. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.002. PMC 3444165. PMID 22939619.

- ^ Nuvolone M, Merlini G (2017). “Emerging therapeutic targets currently under investigation for the treatment of systemic amyloidosis”. Expert Opin Ther Targets 21 (12): 1095-1110. doi:10.1080/14728222.2017.1398235. PMID 29076382.

- ^ Joseph NS, Kaufman JL (2018). “Novel Approaches for the Management of AL Amyloidosis”. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 13 (3): 212-219. doi:10.1007/s11899-018-0450-1. PMID 29951831.