ソープ・インゴールド効果

ソープ・インゴールド効果(ソープ・インゴールドこうか、英語: Thorpe–Ingold effect)、gem-ジメチル効果[1]、またはangle compression[2]は、立体障害が増大することで閉環反応や分子内反応が優先的に起こる、という化学において観察される効果である。Beesley、ソープ、インゴールドによって環化反応の研究の一部として1915年に初めて報告された[3]。以後、本効果は多くの化学分野び一般化されている[4]。

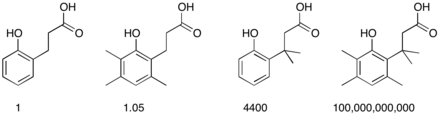

様々な2-ヒドロキシベンゼンプロピオン酸のラクトン形成(ラクトン化)の相対的速度がこの効果の良い例となる。メチル基の数が増えるほど環化過程が加速する[5]。

この効果の応用の1つが、アルキル鎖への四級炭素(例えばgem-ジメチル基)の追加による環化反応の反応速度と平衡定数の増大である。一例はオレフィンメタセシス反応である[6]。ペプチドフォルダマーの分野では、2-アミノイソ酪酸といった四級炭素を含むアミノ酸残基が特定の種類のらせんの形成を促進するために使われる[7]。

この効果に対して提唱されている説明の1つは、置換基のサイズが増大することで置換基間の角度が大きくなる、というものである。その結果として、その他2つの置換基間の角度が小さくなる。それらが互いにより近くに移動することによって、それらの間の反応が加速される。これは速度論的効果である。

In silico研究において、シクロブタンから1-メチルシクロブタン、1,2-ジメチルシクロブタンへと置換基が増えるとひずみエネルギーが8 kcal/mol[8]から1.5 kcal/mol[9]低下していくため、本効果には熱力学的寄与もある。超分子触媒におけるソープ・インゴールド効果の特筆すべき例がグアニジウム基を持つジフェニルメタン誘導体によって示されている[10]。これらの化合物はRNSモデル化合物のHPNPを切断する活性を持つ。ジフェニルメタンスペーサーのメチレン基をシクロヘキシリデンおよびアダマンチリデン基に置換すると触媒効率がそれぞれ4.5および9.1(相対値)に増大する。

出典

編集- ^ Allinker, N. L.; Zalkow, V. (1960). “Conformational Analysis. IX. The Gem-Dimethyl Effect”. J. Org. Chem. 25 (5): 701–704. doi:10.1021/jo01075a006.

- ^ Jack B. Hartung Jr. and Steven F. Pedersen (1989). “A regioselective synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted-1-naphthols. The coupling of alkynes with 1,2-aryldialdehydes promoted by NbCl3(DME)”. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111 (14): 5468–5469. doi:10.1021/ja00196a064.

- ^ Beesley, Richard Moore; Christopher Kelk Ingold; Thorpe, Jocelyn Field (1915). “CXIX.–The formation and stability of spiro-compounds. Part I. Spiro-Compounds from cyclohexane”. J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 107: 1080–1106. doi:10.1039/CT9150701080.

- ^ Shaw, B. L. (1975). “Formation of Large Rings, Internal Metalation Reactions, and Internal Entropy Effects”. Journal of the American Chemical Society 97 (13): 3856–3857. doi:10.1021/ja00846a072.

- ^ Michael N. Levine, Ronald T. Raines (2012). “Trimethyl lock: a trigger for molecular release in chemistry, biology, and pharmacology”. Chem. Sci. 3: 2412–2420. doi:10.1039/C2SC20536J.

- ^ Fürstner, A; Langemann, K. (1996). “A Concise Total Synthesis of Dactylol via Ring Closing Metathesis”. J. Org. Chem. 61 (25): 8746–8749. doi:10.1021/jo961600c. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0024-07AC-2. PMID 11667847.

- ^ Misra, Rajkumar; George, Gijo; Reja, Rahi M.; Dey, Sanjit; Raghothama, Srinivasarao; Gopi, Hosahudya N. (2020). “Structural insight into hybrid peptide ε-helices” (英語). Chemical Communications 56 (14): 2171–2173. doi:10.1039/C9CC07413A. ISSN 1359-7345. PMID 31970340.

- ^ Ringer, Ashley L.; Magers, David H. (1 March 2007). “Conventional Strain Energy in Dimethyl-Substituted Cyclobutane and the gem -Dimethyl Effect”. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 72 (7): 2533–2537. doi:10.1021/jo0624647. PMID 17341119.

- ^ Bachrach, Steven M. (1 March 2008). “The gem -Dimethyl Effect Revisited”. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 73 (6): 2466–2468. doi:10.1021/jo702665r. PMID 18278945.

- ^ Salvio, Riccardo; Mandolini, Luigi; Savelli, Claudia (19 July 2013). “Guanidine–Guanidinium Cooperation in Bifunctional Artificial Phosphodiesterases Based on Diphenylmethane Spacers; gem -Dialkyl Effect on Catalytic Efficiency”. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 78 (14): 7259–7263. doi:10.1021/jo401085z. PMID 23772969.

関連項目

編集外部リンク

編集- cosine (2014年3月10日). “ソープ・インゴールド効果 Thorpe-Ingold Effect”. Chem-Station. 2023年1月18日閲覧。

- cosine (2017年11月27日). “トリメチルロック trimethyl lock”. Chem-Station. 2023年1月18日閲覧。